The legacy of Nordic interaction

There is a long history of substantial political and cultural cooperation among the Nordic countries. For centuries the countries either ruled one another or politically cooperated (Laine, 2020). They are commonly grouped together in terms of political, historical and cultural relationships, in addition to sharing similar languages and geographical proximity. Furthermore, for a long time, there has been a significant flow of people between all the Nordic countries and jurisdictions (Pedersen et al., 2008). Nordic societies share Lutheran pragmatic and democratic ideals, often accompanied by staunch individualism and an enlightened attitude – at least to some extent (Laine, 2020). Within the field of education, there has been an extensive period of considerable interaction, in which Nordic societies have cooperated and often influenced each other at various levels. A Nordic dimension is frequently discussed under the heading of a Nordic model (e.g., Blossing et al., 2014; Prøitz & Aasen, 2017; Tröhler et al., 2023), or a Nordic reference (Karseth et al., 2022), but a broad perspective on various types of interaction within the arena of education is somewhat lacking, even though the field has opened somewhat, as discussed in e.g. Volmari et al. (2022).

The paper focuses on the current situation and recent history. The substantive interaction of the type we describe here has a much longer history, and there are many historical events that form obvious roots to later developments. One example of this is the first Nordic school meeting held in Gothenburg in 1870, and attended by primary school teachers, principals, and administrators. Subsequent meetings of this kind were held roughly every five years until the middle of the twentieth century, see Table 1, where the first fourteen meetings are listed. In these Nordic school meetings, relatively large numbers of education professionals, and sometimes ministers, from the Nordic countries met to discuss various issues. The meetings were held in the different Nordic countries. Some Baltic participants also attended from quite early on.

| MEETING PLACE | NO. OF PARTICIPANTS | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | meeting | 1870 Gothenburg | 842 |

| 2. | meeting | 1874 Kristiania (now Oslo) | 1164 |

| 3. | meeting | 1877 Copenhagen | 1910 |

| 4. | meeting | 1880 Stockholm | 5227 |

| 5. | meeting | 1885 Kristiania (now Oslo) | 3470 |

| 6. | meeting | 1890 Copenhagen | 5300 |

| 7. | meeting | 1895 Stockholm | 6554 |

| 8. | meeting | 1900 Kristiania (now Oslo) | 5563 |

| 9. | meeting | 1905 Copenhagen | 6975 |

| 10. | meeting | 1910 Stockholm | 6962 |

| 11. | meeting | 1920 Kristiania (now Oslo) | 3195 |

| 12. | meeting | 1925 Helsinki | 2655 |

| 13. | meeting | 1931 Copenhagen | 4408 |

| 14. | meeting | 1935 Stockholm | 4410 |

A host of Nordic conferences or meetings of teachers with various specialisations were also held quite regularly during the twentieth century, some of which are lacking documentation. In connection with the Nordic school meeting in Stockholm in 1935, for example, about 500 Nordic and Baltic school kitchen teachers attended their sixth meeting (s. skolköksmöte), also held in Stockholm (Grimlund, 1935, pp. 75–79, 913–922).

In the present paper, we take interaction to have a rather wide reference, including consultation, collaboration and cooperation, but it also involves other modes, such as presenting platforms like Nordic journals. Interaction in this context ranges from students who study abroad in another Nordic country, on an individual basis, to various types of interaction found at the scientific level, including journals and conferences, cooperative discussions on concerns, ideas and policy issues within various fields, and collaboration on tackling issues at the local or global levels. At all levels, the documentary evidence is fragmented, and sometimes even non-existent, regarding both formal and informal interaction. The communicative nature of interaction does not necessarily result in an outcome of any coordinated practical action or policy, but does on occasion result in coordinated policy views, both in Nordic and international settings.

The focus on the interactive aspects of the Nordic scene is motivated by, inter alia, a recent study (Volmari et al., 2022) on regional policy spaces that show how complex Nordic policy cooperation is in the field of education and how informal much of it is – making it difficult to pin down. Thus, we find it important to explore interactions between, but mainly within, different interactive spaces to shed further light on varieties of Nordic educational cooperation, some of which are related to policy discourse but rarely directly. The main aim of the paper is to map out some of the arenas and interconnections within the Nordic educational spaces, and thus to grasp their extent and develop a basis for understanding the rationale of the interactions taking place.

The notion of space and educational spaces

The space metaphor is tempting given that it offers to subsume many different phenomena under one category, as the varied and wide-ranging space literature reflects, by extending a geographical and architectural term to a fundamentally philosophical discussion (West-Pavlov, 2009). Terms such as cultures or societies (see e.g., Massey, 2005, p. 64) seem too broad, but in some cases they manage to convey what is being aimed at in the description. In some cases, platforms or communication arenas could serve as appropriate characterisations. Despite Foucault’s efforts to stretch the term space to extend to “the process of power, confrontation and relations in society” (Raj, 2019, p. 61), here we only refer to the last interactive term, referring to relationships within the Nordic countries – but not forgetting that the Baltic countries often accompany the Nordic. The work of Christmann et al. (2022) moves the space discussion nearer to our concern with their focus on the communicative construction of spaces. The spaces we direct our attention to are socially constructed and characterised by various types of interaction, which are essentially various ways of communication. Thus, drawing on Christmann (2022), the term space (rather than dimension or arena) is used to refer to a socially constructed space, which is defined, for example, by operations, values, culture, and different types and categories of interaction and actions. It is therefore considered fluid and dynamic, and not limited to physical places. The study directs us to the unfolding of different strategies of communication, rather than the different forms of spaces developing (as discussed by Löw & Marguin, 2022).

The spaces we describe are physical or virtual nodes where people, normally professionals at some level, meet directly or in virtual space, to consult for various reasons, in particular about concerns or suggestions for action or for sharing knowledge and understanding. There are basically two types of hierarchical relationship structures among the participants. The first is essentially a binary one where some of the participants are in a learning role and some in a teaching role e.g., students studying or a group on a fact-finding mission or a tour to inspire potential policy-borrowing. The second type is where there is no explicit hierarchy present, and all participants have essentially equal status, e.g., at meetings of administrators, practitioners or academics or even publishing in journals. It would be an exception if a common line of action (e.g., policy) were planned, in any of these spaces, – this absence of striving for a common policy can even be seen as a defining characteristic of most of the spaces we bring to light. The Nordic spaces within our purview are thus normally not oriented towards framing a Nordic policy in the field or at the level in question.

We start by classifying the different spaces with reference to the role they appear to play in society more generally. In the process, we note the dimensions of the spaces and gradually evaluate which emerge as the relevant ones, adding some critique of our approach. We soon move to our main aim, which is to draw attention to the multitude of interactive spaces that populate the field of Nordic education.

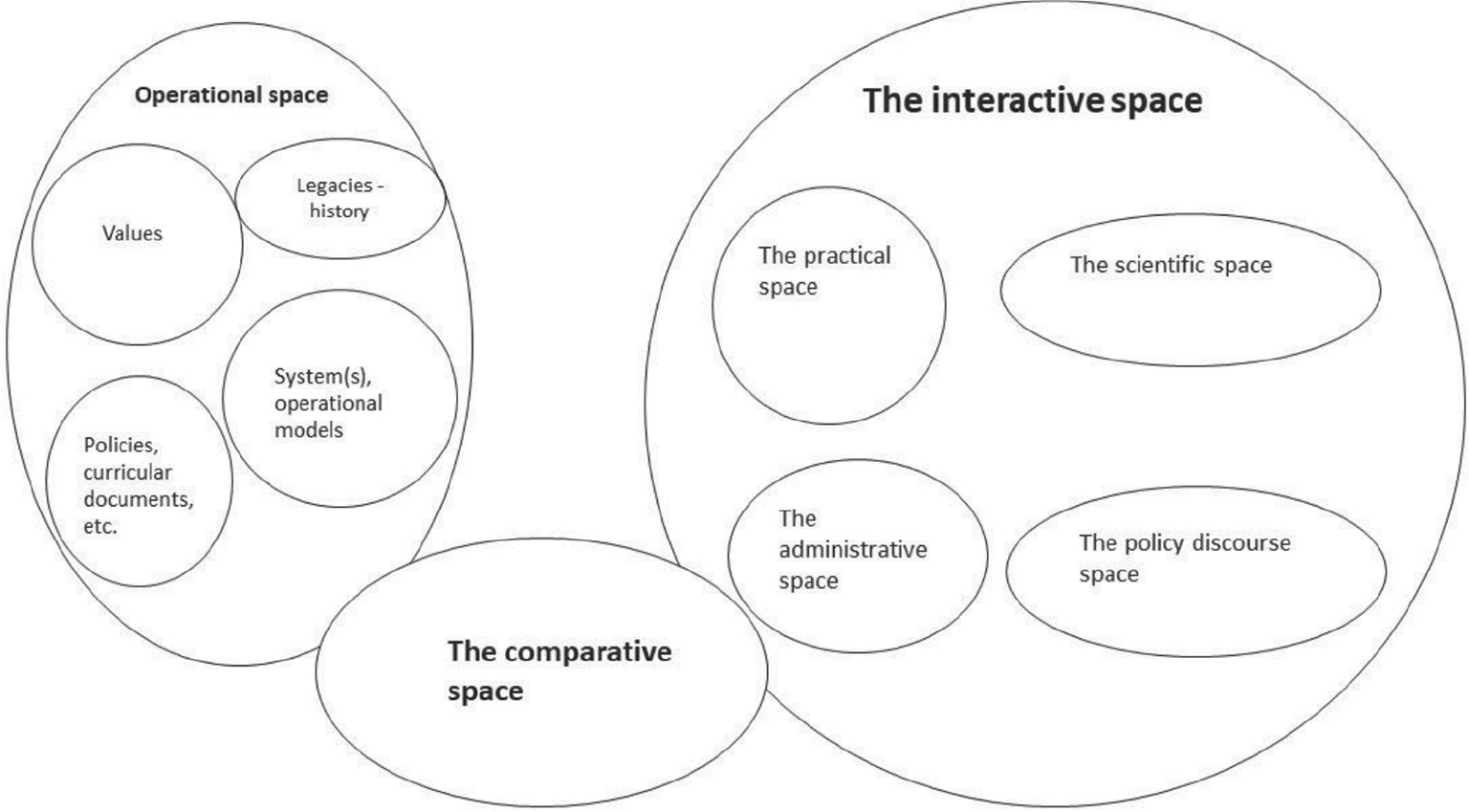

There are three educational spaces constructed for this discussion. These are depicted schematically in Figure 1, also indicating some sub-spaces. First, we note the operational space of education, including the values, structure and practices that dominate and characterise an educational system – we might also call it the system space. Many papers in this special issue focus on aspects of this overarching space and it will not be discussed here. Then we point to our central concern, the interactive space, which refers to manifold interactions at all levels within or attached to the educational system. The third space is the comparative space, where educational outcomes or operational modes are compared, primarily Nordic ones, and which we treat as a separate phenomenon even though it certainly connects to the other two.

Nordic interactive spaces within the arena of education

We show that there is widespread interaction and sometimes cooperation at a multitude of levels within the educational field, played out socially and somewhat informally. Not all of this is documented officially. At many of these levels, this interaction has a long history and even though its intensity has varied considerably there is no sign that it is diminishing overall. Various ongoing projects and initiatives in recent decades provide evidence for such a conclusion.

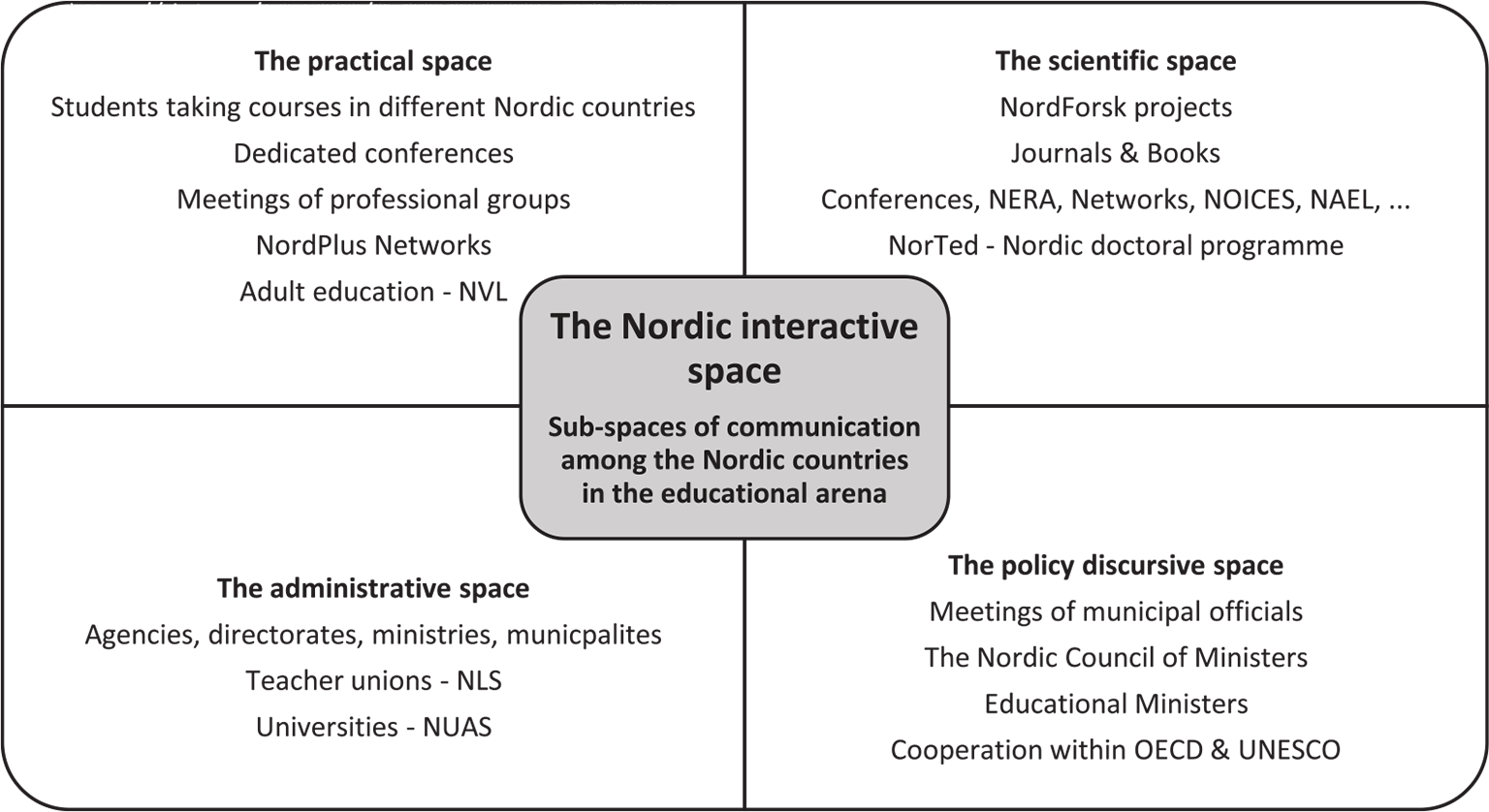

In Figure 2 we suggest four main sub-spaces (Jónasson et al., 2021), within the overarching interactive space, which we will discuss in turn. These are 1) the practical space, where experts or practitioners within specific fields interact in order to consult or co-operate; here we also include students who study abroad in other Nordic countries and forge ties that may last; 2) various scientific sub-spaces which interact in different ways or provide fora for communication and cooperation; 3) the administrative space, where various official, professional bodies or stakeholders or advocacy groups or vested interests meet, in many cases quite regularly; and 4) the local, national, and international policy discussion or consultation arena, or the policy discursive space. Here we use the term “discursive” to emphasise the interaction related to policy issues rather than the actual policy making in individual countries or arenas.

These sub-spaces sometimes overlap; the differentiations and examples shown in the figure are simplified and somewhat limited. There are many types of interactions that constantly take place within any society or groups of close communities. In some cases, there are unidirectional movements of individuals, both short and long-term visits, ad hoc consultation or cooperation and formalised consultation and cooperation. All of these occur at various levels, ranging from individuals to special interest or specialist groups, institutions or formalised societies or governmental bodies, at thelocal, national, or multinational levels. Individual countries also have different priorities and weight within the interactive spaces, as will be pointed out.

Data and sources

We emphasise the exploratory nature of the study. It is based on a literature and docu-mentary search and analysis, consultation with experts on specific aspects of the various types of interactions, including interviews in cases where documentation was lacking. We also draw on our own varied experiences.1

Five key ministerial experts in Iceland, all of whom had long professional experience within the Ministry of Education or the Directorate of Education, were interviewed by both authors and partly reported in Magnúsdóttir and Jónasson (2022) and Volmari et al., (2022). The interviews, which were semi-structured, focused partly on grasping the nature of interactions and cooperation within the Nordic educational arena, particularly within the policy discourse space. The interviewees were promised anonymity and therefore we do not reveal their gender or exact position within the institutions. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. For the purpose of this paper, the analysis focused on providing an understanding of Nordic cooperation and interaction within educational spaces.

In addition to the interview data, we searched for academic journals within the field of education that included “Nordic” or “Scandinavian” in the title and tried to gauge the rationale for the emphasis on these terms in their titles. We did this by exploring their websites as well as by contacting the editors of some of the most recent ones (those established since 2015) and asking them to answer a few questions. We also explored the extent and multiplicity of professional cooperation within NordPlus operational projects, based on the Nordplus website, and then note some NordForsk projects that unite researchers from the Nordic countries. We also asked several colleagues about their experiences of Nordic cooperation. Lastly, we refer to data assembled and reported from other related projects involving at least one of the authors, in particular as shown in Volmari et al., (2022).

The Nordic interactive sub-spaces

Here we will briefly describe some of the activities we place under the four different interactive spaces. By giving examples, we convey the plethora and variety of activities in keeping with the aims of the paper. No attempt was made to make the list exhaustive.

The practical space

Within the practical space we place activities that are quite closely related to school or other educational practice, and we start with two major and related programmes financed by the Nordic Council of Ministers. One is the Nordplus networks programme, which is essentially a funding mechanism for a variety of educational programmes. The other is the Nordic Network for Adult Learning (NVL). Even though both are essentially practise oriented, their content shows quite well how questionable it is to assume any clear-cut categories.

Nordplus networks, financed by the Nordic Council of Ministers, are meant to enhance relationships at the operational or practical level. The programme refers to projects from the eight Nordic areas and three Baltic countries. The programme emphasises its importance by claiming that “educational cooperation starts with Nordplus!” (Nordplus, 2020), which is perhaps somewhat of an overstatement. The programme covers five project areas. The Junior Education programme that extends from kindergarten to the general school system, musical and vocational education; the Nordic Language programme (with emphasis on the Scandinavian languages), the Higher education programme and the Adult education programme. Then there is a Horizontal Education programme that allows for a variety of cross-cutting activities. Nearly half of the funds go to higher education with less allotted to the other programmes. Table 2 shows that over the fifteen-year period in question, typically 300–500 projects have been funded, often with at least three countries taking part.

The Nordic Network for Adult Learning (NVL) was established in 2005 by the Nordic Council of Ministers (NCM), and partly financed through Nordplus. The webpage for NVL (Nordisk netværk of voksnes læring, n.d.) shows how active and multifaceted the Nordic adult education field is, with operational networks focussing on important issues, newsletters, meetings, webinars and with strong links to other, especially European programmes. It is clear how well NVL connects the Nordic countries, also with respect to the national languages. It would probably be difficult to find a current programme that reaches the same level of synergy in the field of Nordic cooperation.

Meetings among various professional groups related to activities noted in Table 1 belong to this category even though these meetings are gradually moving to the scientific space as increasingly professionals are presenting research related material. Documentation of these meetings is particularly difficult to trace.

It is clear that the movement of students facilitated by special agreements between countries belongs to this interactive category (e.g., Agreement concluded by Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden on admission to higher education, 1996), but we consider the interaction too haphazard to be emphasised here.

| NORDPLUS PROJECTS | NUMBER OF PROJECTS FUNDED | ALLOCATION- EURO | NORDPLUS PROJECTS FOR THE YEARS 2008-2022 (NOVEMBER 2022) | HORIZONTAL | NORDIC LANGUAGE | ADULT EDUCATION | JUNIOR EDUCATION | HIGHER EDUCATION | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 442 | 9010604 | |||||||

| 2009 | 482 | 9094151 | |||||||

| 2010 | 512 | 9364525 | |||||||

| 2011 | 507 | 9769183 | Number of projects | 327 | 409 | 748 | 2084 | 2782 | |

| 2012 | 443 | 8947407 | % of projects | 5 | 6 | 12 | 33 | 44 | |

| 2013 | 381 | 9021700 | |||||||

| 2014 | 443 | 10550696 | |||||||

| 2015 | 459 | 10295022 | Amount received | 14534142 | 11294385 | 17753960 | 37552247 | 64245949 | |

| 2016 | 391 | 10004710 | % of funds | 10 | 8 | 12 | 26 | 44 | |

| 2017 | 460 | 10414174 | |||||||

| 2018 | 414 | 9315627 | |||||||

| 2019 | 398 | 10036143 | |||||||

| 2020 | 379 | 10345242 | https://www.nordplusonline.org/ | ||||||

| 2021 | 275 | 8752879 | |||||||

| 2022 | 364 | 10458620 | |||||||

| Total | 6350 | 145380683 | |||||||

Source: Nordplus, project database, November 2022. https://www.nordplusonline.org/

The scientific space

Here we note at least three major categories, a) Various scientific conferences, such as NERA, and its networks, but also conferences on specific narrowly defined areas, such as within mathematics education (NORMA), religious education, vocational education and teacher education, but with a clear scientific flavour; b) NordForsk grants specifically aimed at education; c) Journals and books with a clear Scandinavian or Nordic emphasis. Some of these journals emerge from long-standing regular meetings of the related professional groups.

Below we take a closer look at the journals; there are at least 28 academic journals within the educational arena that have “Nordic” or “Scandinavian” in the title (see Table 3). The oldest journal currently published, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, dates back to 1957, while the most recent ones we found were established in their present form in 2020.

As can be seen by the journal titles, they cover a range of issues related to education. The majority are published in English, but some publish in one or more of the Scandinavian languages. One way to understand better the purpose and rationale of these journals in relation to the Nordic dimension, is to look up their “aims and scope” as presented on their web pages. The editors of some of the most recent journals were also contacted to inquire about the reasons for their specific Nordic emphasis. Here, attention is drawn to three issues regarding the Nordic journals.

| JOURNALS RELATED TO EDUCATION (NORDIC-SCANDINAVIAN) | STARTING YEAR (IN ITS NORDIC FORM) |

|---|---|

| Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research (Pedagogisk Forskning) | 1957 |

| Nordic Studies in Education (Nordisk pedagogik) | 1981 |

| Barn. Forskning om barn og barndom i Norden | 1983 |

| YOUNG Nordic Journal of Youth Research | 1993 |

| NOMAD, Nordisk Matematikkdidaktikk | 1996 |

| Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy (or from 2015) | 2002 |

| Northern lights – PISA+ (every third year) | 2003 |

| Nordina – Nordic Studies in Science Education | 2005 |

| Nordic Journal of Digital Literacy | 2006 |

| Nordand – Nordic Journal of Second Language Research (Nordand – Nordisk) | 2006 |

| Acta Didactica Norden | 2007 |

| Nordisk tidsskrift for utdanning og praksis | 2007 |

| Nordisk Barnehageforskning | 2008 |

| Nordic Journal of Information Literacy in Higher Education | 2009 |

| Nordic Journal of Vocational Education and Training | 2011 |

| Nordidactica – Journal of Humanities and Social Science Education | 2011 |

| Nordisk tidskrift för hörsel- och dövundervisning | 2013 |

| Nordic Journal of Educational History | 2014 |

| The Nordic Journal of Literacy Research | 2015 |

| Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy | 2015 |

| Nordisk Tidskrift för Allmän Didaktik | 2015 |

| Nordisk tidsskrift for pedagogikk og kritikk | 2015 |

| Scandinavian Journal of Vocations in Development | 2016 |

| Nordic Journal of STEM Education | 2017 |

| The Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education (NJCIE) | 2017 |

| Nordisk tidsskrift for ungdomsforskning | 2019 |

| The Nordic Journal of Transitions, Careers and Guidance | 2020 |

| Nordic Research in Music Education (see Yearbook from 1995) | 2020 |

First, even though the journals refer to either Nordic or Scandinavian in their headings, the meanings of these terms are fluid. Some of them are inclusive in the sense that they publish all articles in English, accessible to all the Nordic populations, written in a common lingua franca. Others, but few, are more or less directed towards one or two languages, such as Danish or Norwegian. Those with Scandinavian in the heading include a focus on the Nordic countries in general – showing a broad meaning of the term Scandinavian. Even so, there are examples of Scandinavian being understood in narrower terms, as in the description of the focus and scope of the Nordic Journal of STEM Education (n.d.), “the journal accepts contributions written in English, or the Scandinavian languages (Norwegian, Swedish or Danish)”.

Also, some of the journals seem to attempt to reach a wide international audience while focusing on the Nordic at the same time. For example, the oldest of the journals inspected, The Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research (n.d.), places an emphasis on an international readership and impact while a text about the journal reflecting “ongoing educational research in the Nordic countries” is not limited with regard to its aims and scope. Then there are examples of journals that have the term Nordic in their heading, but do not refer to the Nordic context in their description of focus and scope (Nordic Journal of Transitions, Careers and Guidance, n.d.), presumably either because the Nordic emphasis is taken as given or to make further room for an international emphasis.

The third issue is related to the second, and it is an example of how these journals create a platform for Nordic scholars to benefit from Nordic uniqueness and publish their research in the context of the dominant Anglo-American academic world, or what has been referred to as the hegemonic Anglophone core (Meriläinen et al., 2008; also, Connell, 2017). For example, Aasen et al. (2015), the editors of the journal NordSTEP, noted that one of the aims of the journal was to “contribute to a further strengthening of the Nordic voice in a world dominated by Anglo-American research journals” (p.1) and the aims and scope section says that “[A]rticles published in the journal are not limited to the Nordic educational space, but should relate to, elaborate on, or be of relevance to the Nordic region and Nordic scholarship”. Also, one of the editors of the Nordic Journal of Comparative and International Education remarked the following: “[We] want to provide a space for scholars within the Nordic countries who feel their work is relevant to the overall [comparative and international education] field” (Hólmarsdóttir, personal communication, May 23, 2022). These quotes indicate a willingness to open channels to Nordic voices and research on educational issues, but still remain open to others.

Within the scientific space there are also the activities funded by NordForsk which are rationalised by the notion of “added value” (NordForsk, 2023a). We note as examples the current Education for Tomorrow programme 2013–2023 that funds cooperation and interaction at the Nordic level, e.g., the Nordic Centres of Excellence, JustEd (Justice through Education) and QUINT (Quality in Nordic Teaching) where researchers from all the Nordic countries work together within frameworks that specifically fund interaction, rather than the research activity itself (see NordForsk, 2023b).

A new co-operative venture related to the research arena is Nor-TED, where in 2019 a number of Nordic universities established a doctoral programme cooperation related to teacher education which was essentially a continuation of the Norwegian NAFOL programme (NorTed, 2019).

The administrative space

This space is perhaps the most obscure – (but of course not secretive in any sense). It is apparently well documented (see Nordic Co-operation, n.d.), but one has to know all the venues explicitly in order to retrieve the documentation.2 There are two related aspects of cooperation at the ministerial level, i.e., cooperation in connection with the work of the Council of Ministers, and cooperation connected to independent decisions to consult and cooperate at administrative levels on the basis of the substantive, thematic work of the ministries, which is apparently (by reference to the interviews), facilitated by personal relations established at frequent formal meetings which belong to the policy discursive space.

This also occurs at other levels of the government. The statistical bureaus meet occasionally to focus on educational matters and the directorates of education (which have different mandates in different countries) meet regularly to consult on issues within their purview. Then there are the associations of municipalities who meet regularly, sometimes explicitly to discuss educational issues.

The administrative space also includes independent organisations, such as the Nordic Association of University Administrators [Nordiska Universitets Administratörs Samarbetet] (NUAS) and the Nordic Teachers’ Council [Nordiska Lärarorganisationers Samråd] (NLS). These are very different organisations, both in terms of function and form of interaction, but in both cases, their work is wide-ranging and substantive, and established explicitly to foster Nordic cooperation. NLS consists of sixteen national organisations, representing almost 600,000 professional educators from the Nordic jurisdictions.

These commissions also meet twice a year. The main objective of these meetings is to discuss pedagogical and professional matters, and to exchange information between member organisations. NLS also takes active part in all activities of El [Education International] and ETUCE [European Trade Union Committee for Education]. (Nordiska lärarorganisationers samråd, 2018)

It is clear that this intensive interaction is for consultation, noting concerns and exchanging new ideas, as well as preparing for a coordinated representation in the international forum. NUAS is also a sizable forum of 65 Nordic universities, which have plenary meetings every eighteen months, but they also have fourteen interest groups, which regularly hold their own conferences (NUASkom, 2022).

The policy discourse space

Interactions within formal political institutions, such as the annual Nordic Council meetings, the Nordic Council of Ministers, and Nordic cooperation within international organisations, such as OECD and UNESCO, is the main focus here. Within this space, interactions take place in formal venues, especially within the Nordic Council, where interactions seem to be organised rather informally, according to the experts that we interviewed. The policy discourse referred to here at the Nordic level is normally not about the formation of common policy, such as Nordic policy or national policy, but about cooperation (e.g., Nordisk Ministerråd, 2019) and consultations about the substantive and possibly political concerns that might justify policy change, what policy initiatives are being discussed, how policy has fared, and possible cooperation or a common stance on certain issues.

In international organisations such as the OECD, the interactions have a different focus, and are rather related to consulting about the stance to be taken on the issues under discussion. It is important to note that even though accounts from Iceland are present in the Nordic context, they mirror accounts by experts from the other Nordic countries, e.g., as presented in Volmari et al. (2022).

The most prominent narrative presented by the experts was that interactions within the larger Nordic policy arenas were highly reliant on informal meetings prior to larger formal meetings. It was evident how these interactions are shaped by traditions and informal cooperation, without formal records or other formal procedures. At the meetings, the Nordic and Baltic representatives, according to one of the experts, examine the agenda and attune themselves to each other by asking questions such as:

are we going to apply us collectively in any case? … [One member might say:] ‘we may take this up and would you be willing to support it’, or something like that. And this is, in all these committees, or both within the EU and OECD, that I have experienced this.

Another expert, who had also participated in such meetings said that “usually there is not a particular Nordic position to matters, but still, people coordinate … if the Nordic countries want to take the lead in some issues, they coordinate it there”. Further, “the Nordic countries have a lot of impact in there, they are always, or usually, in agreement. Then they have great influence. One takes the floor, and the others give support”.

This seems to be the case within UNESCO as well. Another expert told us that “the Nordic group is in charge … it works very closely together. They are e-mailing during the meetings, ‘are Iceland or Denmark going to talk about this?’, you know, very intensive relationship.” This was explained further by yet another expert, who said that “it does not even need mentioning that the Nordic countries, in everything that I have participated in, are extremely strong together”. Thus, from the outside, the Nordic countries operate as one entity in this international collaboration. However, some countries have greater manpower than others and they are consequently in stronger power positions within this cooperation (see also Magnúsdóttir & Jónasson, 2022).

It is not all plain sailing, however. The idea of the Nordic countries as a single harmonious unit with equal impact and power, can be contested, noting a comment by one interviewee who suggested that sometimes the Nordic countries gave the impression of “a dysfunctional family” – further suggesting the importance of looking at the Nordic educational space as a complex social construct rather than limited to geographic or cultural unity. The presence of the Baltic countries within this interactive space also supports this.

The comparative space

Comparison between the Nordic countries looms large in the Nordic educational discourse, as is clear from many chapters in Karseth et al. (2022) and the current special issue. This comparison is largely related to performance data (e.g., Nordic PISA results) or to how different parts of the school systems are organized. However, performance data and school systems do not fit perfectly into the operational space or the interactive space, even though they connect to both. They are therefore presented here as a special educational space, the comparative space. This space normally involves direct comparison between the Nordic countries, often by policy makers, administrators or educational leaders who use such comparison as evidence or reference points for the need to act or change, in order to respond to unfavourable comparison, or perhaps to explain that nothing much needs to be done. Here the Nordic countries become a very special case in the national debates.

The Nordic comparison seems to be the default, not least in relation to PISA and other international indicators. As one of the experts explained:

When we are looking at the results, both in PISA and TALIS, then we compare ourselves to the Nordic countries. And I mean, being the lowest of the Nordic countries is actually worse than being below the OECD average. I experience it like that … we want to be close to them and we want to compare to them … because we identify with them.

The importance of the Nordic comparison is due to a combination of practical and socio-cultural reasons. For example, regarding the Nordic comparison, one expert said that it was “perhaps easier to get information about [all kinds of data] and people look towards similar systems, with a comprehensive school system … because their systems are similar to ours”. Also, it was mentioned how convenient it was to collect data about the other Nordic school systems, since the officialdom know each other via the policy discourse space. The data was seen to be accessible, the systems seen to be both familiar and similar and culturally related and thus the comparison was seen as more valid than comparing to other systems.

This comparative space was clearly evident in some of the chapters in the deliberations about Nordic evidence in Karseth et al. (2022) often based on the OECD PISA studies or kindred material. The reference is to national policy initiatives based primarily on Nordic comparison. Here there is overlap with the interactive space; the same data is used in various research literature, e.g., the Northern lights volumes (Nordic Council of Ministers, 2018) or various comparative studies (Albæk et al., 2015; Jónasson & Tuijnman, 2001). Two recent reports on challenges faced by education published by the Nordic welfare centre are based on extensive Nordic comparison (Broström & Jansson, 2022; Eriksson, 2021). These reports claim that the Nordic comparison gives a rise to a call for action. This is much in accord with what we deduce from the interviews concerning how far the experts would go in their consultative approaches.

Conclusions and discussion

Here, we have endeavoured to map out at least some of the interactions, dimensions and sub-spaces within the Nordic educational spaces. To a certain extent, we have also enhanced the understanding of the rationale behind these interactions. We have indicated how multidimensional, complex, and often hidden, these interactions are. We have also hinted at how many different dimensions emerge as we begin to discuss these different spaces.

We find that Nordic interactive activity within the field of education is massive and of widely differing types. We are convinced that there are still many activities that we don’t know about. Interestingly, many new Nordic projects are taking off in the educational field, and we have probably only detected some. It is difficult to assess the extent of this activity, as in many cases, the documentation is either lacking or meagre and therefore difficult to access. This applies to all of the interactive spaces mapped out here, not least the administrative space. Therefore, the activities are normally not known outside fairly restricted groups, and it is not clear for those on the outside what to look for or where. This presents a methodological challenge when assessing the amount and scope of the interaction. Perhaps this is the reason why academia’s interest in exploring the interactive space and its rationale has seemingly been limited. We have not found a concerted effort to draw a map of the various interactive spaces and we even sense a tendency to ignore it. The signifier of Nordic cooperation floats towards documented arenas. However, it is clear that there is much more to the Nordic interactive spaces than what is officially or scientifically documented and some documents that presumably exist are even difficult to find. This lack of available documentation was one of the conclusions of Volmari et al., (2022). Here we have pieced together some additional bits of knowledge on the interactive spaces in the Nordic field of education.

In an attempt to map these interactions, we have found it helpful to conceptualise them in line with what Christmann et al. (2022) term communicative construction of spaces. This conceptualization acknowledges the complex entanglements of socially constructed spaces, interconnected to geographic, cultural, historical, and communicative factors. Still, it is difficult to characterise the various types of interactions we find, and therefore we note that while the differentiation we suggest is helpful, it is clearly a simplification. Also, the notion of the Nordic is fluid, i.e., because it can both be limited to some, or all, of the Nordic countries or jurisdictions and expanded to include the Baltic countries as well and has been so for a long time.

In previous research on the Nordic dimensions in education, it has proven helpful to use a long-term perspective (Jónasson et al., 2021). However, we have not done that here, even though we have hinted, using one example, that some activities like those we have described have a long history. This lack of a historical perspective is mainly because of the difficulty in obtaining information, let alone time series for some of the activities. The early activities have clearly developed in many different directions.

Partly explicit but definitely implicit in our work is an attempt to clarify which dimensions might be relevant for describing the spaces we have taken up, including a wide variety of examples. Each of the spaces we have noted has a number of potential dimensions, even if our discussion has only emphasised two. One is the occupational role of the participants. This we consider as the principal dimension since we see this reflecting the content of the interaction taking place, even if this classification does not reflect a pure category. Thus, the scientific level of journals may vary somewhat whereas the ingredients of the NordPlus programmes vary substantially, as does the hierarchical level of the administrative groups that meet regularly. The other dimension which we emphasise is the nature of the intended interaction, e.g., learning, fact finding, collaboration, cooperation, consultation, production of scientific evidence; people interact for various synergetic reasons. This is what we consider the most relevant and intriguing dimension and suggest that it most urgently and interestingly calls for further inquiry.

There are clearly additional dimensions to discuss, i.e., time which is perhaps most commonly discussed in the literature on space. In the present context, however, we have observed the level of documentation emerging from the interaction taking place (which is normally low), which may be an important indicator of how the participants view the activity; the number of participating nations represented – assuming that at least two need to be present for the activity to fall within the category of Nordic interaction; the actual language used for communication (a Scandinavian language or English); and the number of people representing each nation, which may range from one to many hundred. It goes without saying that there are of course national interactive spaces, but there, we assume, in addition to the above-mentioned characteristics we are more likely to find a discussion about a common position or policy.

Lastly, we note that the rationales for Nordic interaction are multi-faceted, which in essence is no different from the rationales for domestic or international cooperation. There can be a wish for synergy, as with conferences, academic journals, grants and research projects, which may both involve cooperation, collaboration or the informal interaction of individuals and institutions within different Nordic countries. People are looking for knowledgeable people, professionals or other experts, who are dealing with similar issues, worries, and concerns; and comparing notes, deliberating on weaknesses, receiving ideas and discussing them. One of the rationales is also the wish to have a similar context to compare to, and therefore, the Nordic comparison seems to become the default setting in the comparative space. With students, workers, academics, and professionals moving between the Nordic countries, knowledge is shared, networks are created, and collaboration becomes both natural and convenient. This creates an impact even though we might not be able to pinpoint it, and it is not directly related to policy making.

An interesting set of rationales is related to the political sphere, with a focus on synergy, reflected in activities financed by political bodies, such as the activities of NordPlus, NordForsk and NVL. Obviously, extensive collaboration promotes unity between the Nordic countries. They can have more impact united than they can as five (or eight) individual nations or jurisdictions. Within the scientific space, the Nordic research and project funds can simultaneously develop Nordic expertise and values. Thus, rationale related to politics apply to both interactions within and outside the Nordic countries.

We have shown that there are many programs and collaborative activities on the professional side related to the field of education. What these programs actually deliver to the various arenas we do not know, but there can be no doubt that the impact varies. These kinds of activities are, of course, not limited to the Nordic countries, but we know that this kind of interaction has a long tradition in the Nordic arena and we are convinced that it is much more extensive than is often realised.

It is difficult to assess how well the overall picture or map that we have sketched is known to professionals in the educational field. We suspect, from our own experience, that each node knows precious little about the others, and thus, the extent of Nordic cooperation might not be well known even to insiders. No attempt has been made to assess this nor to gauge the influence of the various activities that we have noted. Nor have we explored potential interactions between the three educational spaces, in particular how much influence the interactive spaces or the comparative space really have on the operational space. While that would be an important next step, the influence of the interactions is not easy to assess, and conversations, collective work, and activities that are assumed to be valuable, are normally particularly difficult to measure. This is one of the methodological challenges this area faces. It can nevertheless be assumed that these interactions, on different levels and within and between different spaces, have value in themselves, and in the context in which they take place. This is what inspires and sustains the plethora of activities observed.

REFERENCES

- Agreement concluded by Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden on Admission to Higher Education, adopted in 1996. https://www.norden.org/en/declaration/agreement-concluded-denmark-finland-iceland-norway-and-sweden-admission-higher

- Albæk, K., Asplund, R., Barth, E., & Lindahl, L. (2015). Youth unemployment and inactivity: A comparison of school-to-work transitions and labour market outcomes in four Nordic countries. Nordisk Ministerråd. https://issuu.com/nordic_council_of_ministers/docs/9789289342292

- Blossing, U., Imsen, G. & Moos, L. (Eds.). (2014). The Nordic education model. ‘A school for all’ encounters neo-liberal policy. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-7125-3

- Broström, L. & Jansson, B. (2022). Leaving boys behind? The gender gap in education among children and young people from foreign backgrounds 2010–2020: A Nordic review. Nordic Welfare Centre. https://nordicwelfare.org/en/publikationer/leaving-boys-behind/

- Christmann, G. B. (2022). The theoretical concept of the communicative (re)construction of spaces. In G. B. Christmann, H. Knoblauch, & M. Löw (Eds.), Communicative constructions and the refiguration of spaces: Theoretical approaches and empirical studies (pp. 89–112). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367817183

- Christmann, G. B., Knoblauch, H., & Löw, M. (2022). Communicative constructions and the refiguration of spaces: theoretical approaches and empirical studies. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367817183

- Connell, R. (2017). Southern theory and world universities. Higher Education Research and Development, 36(1), 4–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1252311

- Eriksson, C. (2021). School achievement and health development in the Nordic countries. Knowledge gaps and concerns about school-age children. Nordic Welfare Centre. https://nordicwelfare.org/en/publikationer/school-achievement-and-health-development-in-the-nordic-countries/

- Grimlund, H. (1935). Fjortonde nordiska skolmötet Stockholm 1935 [The 14th Nordic School Meeting]. Ernst Westerbergs Boktryckery A.-B.

- Jónasson, J. T., & Tuijnman, A. (2001). The Nordic model of adult education: Issues for discussion. In A. Tuijnman & Z. Hellström (Eds.), Curious minds. Nordic adult education compared (pp. 116–128). TemaNord & Nordic Council of Ministers.

- Jónasson, J. T., Bjarnadóttir, V. S., & Ragnarsdóttir, G. (2021). Evidence and accountability in Icelandic education – an historical perspective? In J. B. Krejsler & L. Moos (Eds.), What works in Nordic school policies? Mapping approaches to evidence, social technologies, and transnational influences (pp. 173–194). Springer https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783030666286

- Karseth, B., Sivesind, K., & Steiner-Khamsi, G. (Eds.). (2022). Evidence and expertise in Nordic education policy: A comparative network analysis. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91959-7

- Laine, J. (2020). Nordic cooperation. In W. Wassenberg & B. Reitel (Eds.), Critical dictionary on cross border cooperation in Europe (pp. 615–625). Peter Lang. https://doi.org/10.3726/b15774

- Löw, M., & Marguin, S. (2022). Eliciting space. Methodological considerations in analyzing communicatively constructed spaces. In G. B. Christmann, H. Knoblauch, & M. Löw (Eds.), Communicative constructions and the refiguration of spaces: Theoretical approaches and empirical studies (pp. 113–135). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367817183

- Magnúsdóttir, B. R., & Jónasson, J.T. (2022). The irregular formation of state policy documents in the Icelandic field of education 2013–2017. In B. Karseth, K. Sivesind & G. Steiner-Khamsi (Eds.), Evidence and expertise in Nordic education policy: A comparative network analysis. Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91959-7

- Massey, D. B. (2005). For space. SAGE.

- Meriläinen, S., Tienari, J., Thomas, R., & Davies, A. (2008). Hegemonic academic practices: Experiences of publishing from the periphery. Organization, 15(4), 584–597. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508408091008

- NordForsk. (2023a). How does research cooperation lead to Nordic added value? https://www.nordforsk.org/how-does-research-cooperation-lead-nordic-added-value

- NordForsk. (2023b). Education for tomorrow. https://www.nordforsk.org/programs/education-tomorrow

- Nordic Co-operation. (n.d.). Education and research. https://www.norden.org/en/education-and-research

- Nordic Council of Ministers. (2018). Northern lights on TIMSS and PISA. Nordic Council of Ministers. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1237833/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Nordic Journal of STEM Education. (n.d.). About the journal. https://www.ntnu.no/ojs/index.php/njse/about

- Nordic Journal of Transitions, Careers and Guidance. (n.d.). Focus and scope. https://njtcg.org/about/

- Nordisk Ministerråd. (2019). Nordisk samarbejdsprogram for uddannelse og forskning 2019–2023. https://norden.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1365361/FULLTEXT02.pdf

- Nordisk netværk for voksnes læring. (n.d.). Om NVL. https://nvl.org/om-nvl/in-english

- Nordiska lärarorganisationers samråd. (2018). Welcome to NLS – Nordic Teachers’ Council. https://nls.info/en/

- NordPlus. (2020). Nordic and Baltic cooperation. https://www.nordplusonline.org/

- NorTed. (2019). NorTED – Nordic research school in teacher education relevant research. http://nor-ted.com/

- NUASkom. (2022). About NUASkom. https://nuaskom2022.fi/about-nuaskom

- Pedersen, P. J., Røed, M., & Wadensjö, E. (2008). The common Nordic labour market at 50. Nordic Council of Ministers. 10.6027/TN2008-506

- Prøitz, T. S., & Aasen, P. (2017). Making and re-making of the Nordic model of education. In P. Nedergaard and A. Wivel (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of Scandinavian politics. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315695716

- Raj, E. (2019). Foucault and spatial representation. PILC Journal of Dravidic Studies, New Series, 3(1). https://ssrn.com/abstract=3644784

- Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research. (n.d.). Aims and scope. https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?show=aimsScope&journalCode=csje20

- Tröhler, D., Hörmann, B., Tveit, S., & Bostad, I. (Eds). (2023). The Nordic education model in context. Historical developments and current renegotiations. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Nordic-Education-Model-in-Context-Historical-Developments-and-Current/Trohler-Hormann-Tveit-Bostad/p/book/9781032110462

- Volmari, S., Sivesind, K., & Jónasson, J. T. (2022). Regional policy spaces, knowledge networks, and the “Nordic other”. In B. Karseth, K. Sivesind, & G. Steiner-Khamsi (Eds.), Evidence and expertise in Nordic education policy: A comparative network analysis (pp. 349–382). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91959-7_12

- West-Pavlov, R. (2009). Space in theory. Kristeva, Foucault, Deleuze. Rodopi.

- Aasen, P., Forsberg, E. & Petterson, D. (2015). Preface. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 1, 1. https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v1.27012

Fotnoter

- 1 Both authors have participated in Nordic projects. Relatively recently the first author worked for the Nordic Council, UNESCO, PISA-Northern lights, NordForsk, NUAS, NVL, NLS, participated in NERA and the JustEd research project, and contributed to various more narrowly defined educational projects.

- 2 Only by thoroughly exploring all the sub-links is it possible to obtain an impression of all the Nordic activities that take place explicitly within this forum and even then, the multitude of meetings don’t emerge except by looking by month and year. Neither meeting agendas nor substance is available on these webpages.