A curriculum perspective on bullying prevention

The global quest for educational excellence has resulted in an increased emphasis on social and emotional learning in schools (Durlak et al., 2011; Heckman & Kautz, 2013). Mirroring this concern, the OECD now includes rates of bullying in its framework for individual well-being and social progress (OECD, 2015, 2018). Building resilience though social and emotional learning, it is argued, may help reduce bullying involvement and associated long-term health and social costs. The OECD is highly influential (Pettersson, 2014; Pettersson et al., 2017) in setting the agenda for curriculum development in many countries. In Norway, for example, the national government emphasises the development of social and emotional skills as an integrated part of both core and subject curriculum in the ongoing revision of the Norwegian national curriculum (Norwegian Ministery of Education and Research, 2016). In Finland such revisions are already manifest (Halinen, 2018) in a new integrative national curriculum focusing on school culture and student well-being.

The Nordic countries have long been at the forefront of bullying research with internationally acclaimed efforts such as the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program and the KiVa anti-bullying programme (2014; 2018). Nordic scholars, notably Søndergaard (Søndergaard, 2014; 2018) and colleagues have contributed to a new understanding of and novel approaches to the integration of social and academic learning to prevent bullying in schools. Thornberg and colleagues (Thornberg, 2011; Thornberg, Wänström & Jungert, 2018; Thornberg, Wänström & Pozzoli, 2017) have emphasized moral climates among peers and call for more pedagogical research on bullying to “address all the processes that go on in school, and how these processes may produce but also counteract bullying” ( Thornberg, Baraldsnes & Saeverot, 2018, p. 295). In a recent special issue of Nordic Studies in Education, Horton (2018) argues that scholastic competition may drive teachers to emphasise delivery of the official curriculum over dealing with issues of bullying in their classrooms. So far, however, no studies have systematically investigated how curriculum is understood in bullying research or how curriculum perspectives can add new insights to bullying prevention in schools.

In this article I employ a broad concept of curriculum as content, framework and enactment in schools. Building on curriculum theory I use curriculum dimensions (Dillon, 2009), curriculum narratives (Elgström & Hellstenius, 2011) and system ontology (Bhaskar, 2008, 2016; Brown, 2009; Priestley, 2011; Tikly, 2015) as concepts to analyse curriculum understanding in bullying research. This framework is used to address theoretically curriculum understanding and highlight pedagogical constraints imposed by such an understanding as a key component of bullying prevention in schools. The current approach is inspired by a critical research review (Suri, 2013) and critical realism (Bhaskar, 2008, 2016), to identify gaps and critically examine strong ideas in bullying research. To this end, I answer two questions: How is curriculum understood in contemporary research on bullying, and how can a curriculum perspective add new insights to bullying prevention in schools?

Addressing curriculum understanding in bullying research

In preparation for this study, I identified six systematic reviews of bullying research using a combination of database searches and snowball sampling (Cohen, 2018). I read the selected reviews for an overview of the field and to inform the search and coding strategies. In the following, I give a brief outline of how these studies have addressed curriculum in bullying research.

Vreeman and Carrol (2007) investigated the use of curriculum to prevent bullying, including videotapes, lectures, and written curriculum applied in the classroom. They found only four out of ten studies with documented reductions in bullying rates. They also found that comprehensive whole-school approaches that included classroom curriculum had a greater chance of success. Rigby and Slee (2008) found modest effects of standalone curriculum interventions, concluding that “when curriculum work focuses upon the teaching of appropriate social skills, the outcomes are less successful than when a whole-school approach is employed” (p. 177). Farrington and Ttofi (2009; 2012) found that programmes of longer duration, higher intensity and a greater number of components had a greater chance of reducing bullying. Researchers, however, have also cited fears that longer time commitments may be a barrier to the ability and willingness of teachers to participate in such programmes.

In a review of efforts to prevent cyberbullying, Cassidy et al. (2013, p. 587) argue for the need to move “beyond merely teaching about cyberbullying”. Efforts should focus on both the formal and informal curricula of schools and accommodate the rapidly changing nature of cyberbullying by including students in the development of curriculum and by continuously revising content in line with what is current and projected in the media. Tancred and colleagues argue that integrated approaches to prevent substance abuse, violence and bullying aimed “not only to integrate the teaching of health and academic education but also to bridge the relationship between staff and students so that affective bonds are strengthened, teachers serve more effectively as role models and students become more engaged in school” (Tancred et al., 2018, p. 2). Researchers contend that such approaches are underdeveloped but may support local adaptation and professional autonomy in dealing with time constraints and resource limitations in schools.

Several points from these reviews are relevant to the current study. First, studies highlighted bullying curriculum as an essential component of both standalone and whole-school interventions. Second, the reviews demonstrated how bullying prevention may be integrated both in and across subject curriculum. Third, studies emphasised bullying prevention through both formal and informal curricula. Together, these reviews highlight curriculum as a relevant concept in bullying research. Before I explore how this concept is understood in current research, I will briefly present my analytical framework building on curriculum theory and critical realism.

Curriculum theory as an analytical framework

How can we understand the concept of curriculum, and how can it be applied to an analysis of the field of bullying research? Initially, this seems like a difficult question to answer considering that there is little agreement among researchers on how to define curriculum (Dillon, 2009). On a societal level Pinar sees curriculum as “the site on which the generations struggle to define themselves and the world” (Pinar et al., 1995, p. 848). Westbury (1998) understands curriculum at the institutional level, as defining the role of school in culture and society as educational policy, and at the classroom level, as an event initiated by the teacher and jointly developed with the students as an educative experience. Other scholars (Mølstad & Hansén, 2013) have described curriculum as a process of governance whereby actors in power leverage control over who is able to influence the curriculum. Westbury (1998) has further argued that there are important differences between American and European curriculum traditions. One such difference, is the American emphasis on curriculum explicitly directing teachers in both content and methods of delivery. This contrasts with the influential German Didaktik tradition, which sees curriculum as a selection of content that must be embedded through the self-determined work of teachers. The role of the teacher, then, represents a major point of contention between the two traditions, the European tradition favouring teachers as curriculum-makers and the American view of teachers as curriculum-deliverers.

Young has described the task of curriculum theory in this way: “to identify the constraints that limit curriculum choices and to explore the pedagogic implications that follow” (Young, 2013, p. 103). Another way of exploring such constraints is through curriculum dimensions (Dillon, 2009), using the ‘what’-question to analyse curriculum by its nature (what is it?) and content (what is in it?). Further, the ‘how’- question addresses methods of curriculum delivery, while the ‘who’-question focuses on the overarching structures (who decides?) but also on the actors (who does what to whom?) engaging with the curriculum. Finally, the ‘why’ question highlights the purpose of the curriculum in terms of desired student outcomes or societal needs. Adding to this, Elgström and Hellstenius (2011) analyse curriculum as narratives. Starting with the perennialist narrative, they describe a curriculum rooted in tradition and cultural heritage, conveying knowledge in the form of classical literature and historical discoveries. In the essentialist narrative, the curriculum conveys evidence-based knowledge and emphasises the relationship between science and teaching. Progressivism links curricula with contemporary societal problems, emphasising adaptation through participatory and integrated approaches. Finally, reconstructivism sees curriculum as conveying knowledge to transform society in radical ways, fostering critical citizens who question existing structures and engage with contentious political issues.

Building on critical realism, schools can be seen as “stratified, comprising individuals, social groupings and the school as a whole” (Priestley, 2011, p. 228). Tikly has argued that schools are open systems, and should not be treated “as if they were closed systems with the possibility of producing replicable and generalisable results on which to base predictions” (Tikly, 2015, p. 239). Others see the learning environment of schools as “open or at most quasi-closed” (Brown, 2009, p. 31), meaning that what is enacted in schools may appear planned and regular, but never fully corresponds with the law-like tendencies of closed systems. For Priestley, education systems exhibit cycles of change and continuity “as new cultural, structural and individual properties emerge, and as existing patterns are perpetuated” (Priestley, 2011, p. 231). The education system then, from a critical realist perspective, can be seen as a product of continuous interplay between structure and agency at different levels, and the curriculum as one of many causal factors contributing to the emergence of that system.

In this article, I address the constraints imposed by current understandings of curriculum in bullying research. I use curriculum dimensions, curriculum narratives and system ontology as concepts to theoretically explore these constraints. My aim has been to expose gaps that limit the application of pedagogical knowledge in bullying prevention and to bridge two research traditions to pave way for new insights. Such bridging requires not only respectful inquiry and conscientious dialogue, but also rigorous critique. In the following I outline my methodology for the critical review of bullying research.

Conducting the critical research review

This review was inspired by a critical synthesis approach. Suri (2013) has argued that the purpose of the research synthesis is “to produce new knowledge by making explicit connections and tensions between individual study reports that were not visible before” (p. 889). The aim of the synthesis is not only to summarise but also to enhance multiple discourses and refute simplistic explanations. Typical questions asked in the synthesis include, what are the gaps in the prevailing understanding, what methodologies are employed, and whose questions have received insufficient attention. It employs an eclectic and methodologically inclusive approach allowing for both qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods studies in the corpus. Similarly, the concept of immanent critique as described by Bhaskar (2016, p. 3) involves an internal critique of intrinsic ideas or positions held in a particular field of research. In its purest form it seeks to identify weaknesses or blind spots in ideas deemed the weightiest in the field by their proponents.

Building on my initial reading of systematic reviews, I conducted a preliminary search following six lines of inquiry: 1) “Standalone” “curriculum” “bullying,” 2) “Bullying curriculum” “whole-school approach,” 3) “Bullying” “subject curriculum,” 4) “Bullying curriculum” “media” “citizenship,” 5) “Bullying” “informal curriculum,” 6) “Bullying” “integrated curriculum.” This generated a comprehensive body of literature of varying relevance to the current study. Search procedures were subsequently revised, limiting the scope to English language peer-reviewed articles from 2009 to 2019, containing the keywords/topics ‘bullying AND curriculum’. English language journals were preferred in order to gauge how bullying researchers address curriculum issues in their published work, and in dialogue with colleagues from around the world. Limiting the search to studies from the last decade significantly reduced the number of items for review, while still retaining a corpus fit for purpose in this study.

The main search was conducted on 6 March 2019 using the Web of Science, Scopus, and ORIA databases. These databases were selected to ensure a broad representation of studies from the natural and social sciences, and the humanities from both Nordic and international contexts. This search returned in excess of 100 articles from each database. I added additional criteria to exclude studies related to preschool, higher/teacher education, disability/special education, workplace, nursing, and nursing education. Exclusion criteria were derived from the purpose of the study, namely, to investigate curriculum understanding in bullying research in general compulsory education. Although studies of bullying prevention in related fields such as in preschool and kindergarten (see Helgeland & Lund, 2017; Repo & Repo, 2016; Repo & Sajaniemi, 2015) address similar issues, such studies were considered less relevant for the purpose of this review. Similarly, although certain groups, such as students enrolled in special education (Juul, 1989; Rose et al., 2009), have been shown to have a higher risk of bullying victimization, differentiation based on bullying prevalence and students groupings was deemed of minor consequence in the current study.

A total of 54 abstracts were identified and reviewed. Ten articles were excluded for lack of peer review, full text in English, and relevance. Five additional articles from frequently cited anti-bullying programmes (KiVA and Second Step) were removed to prevent overrepresentation. The most recent and relevant studies from both programmes were included.

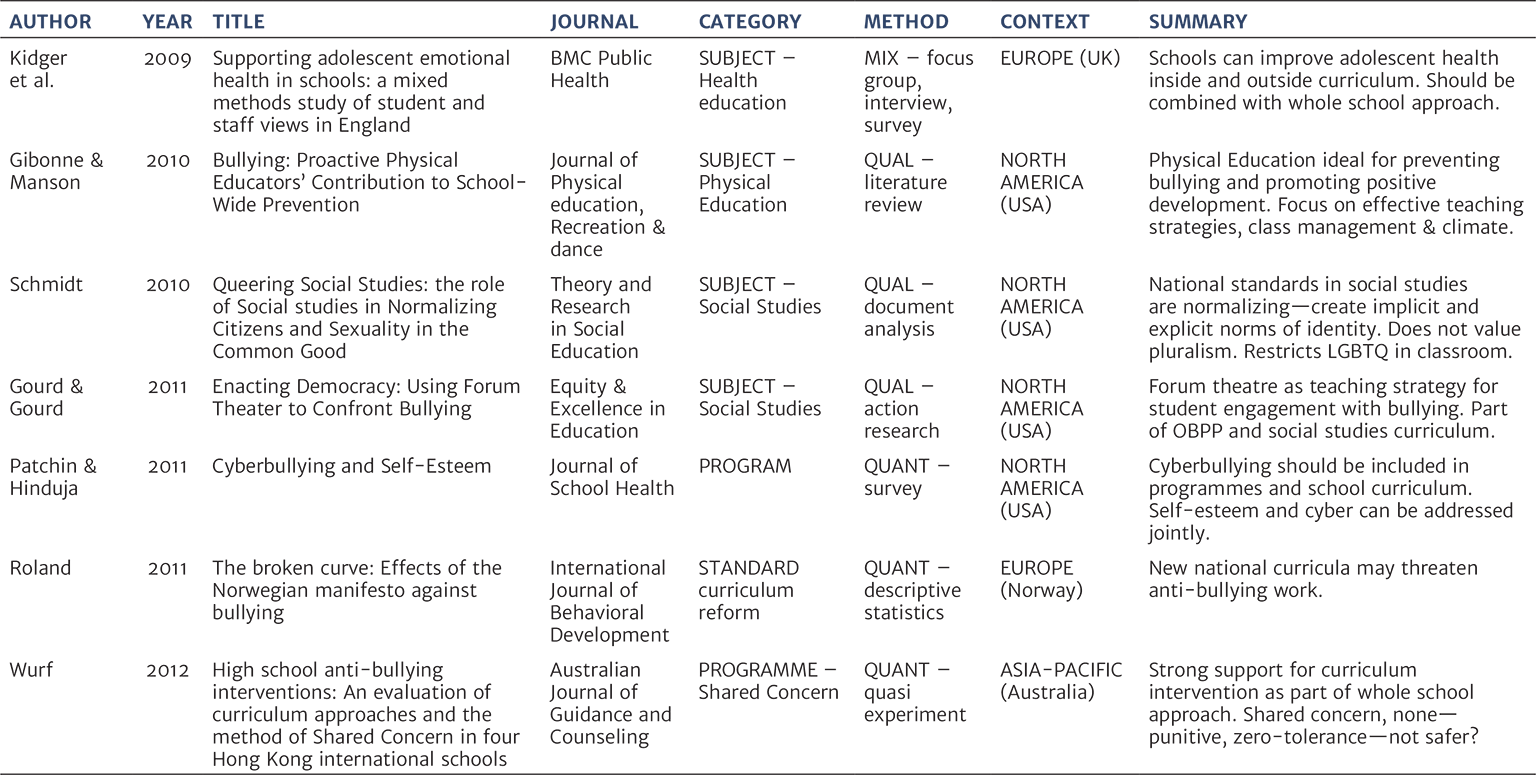

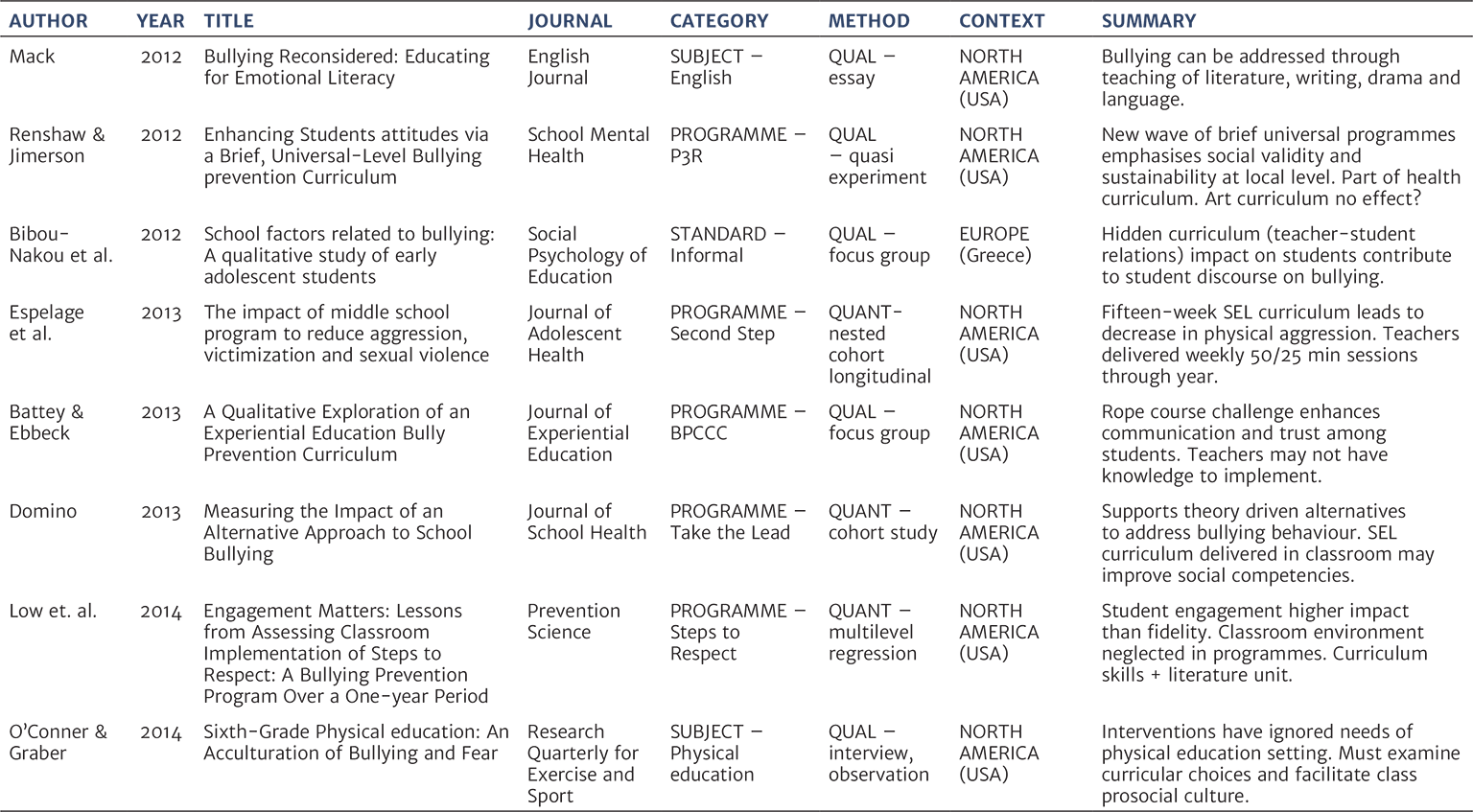

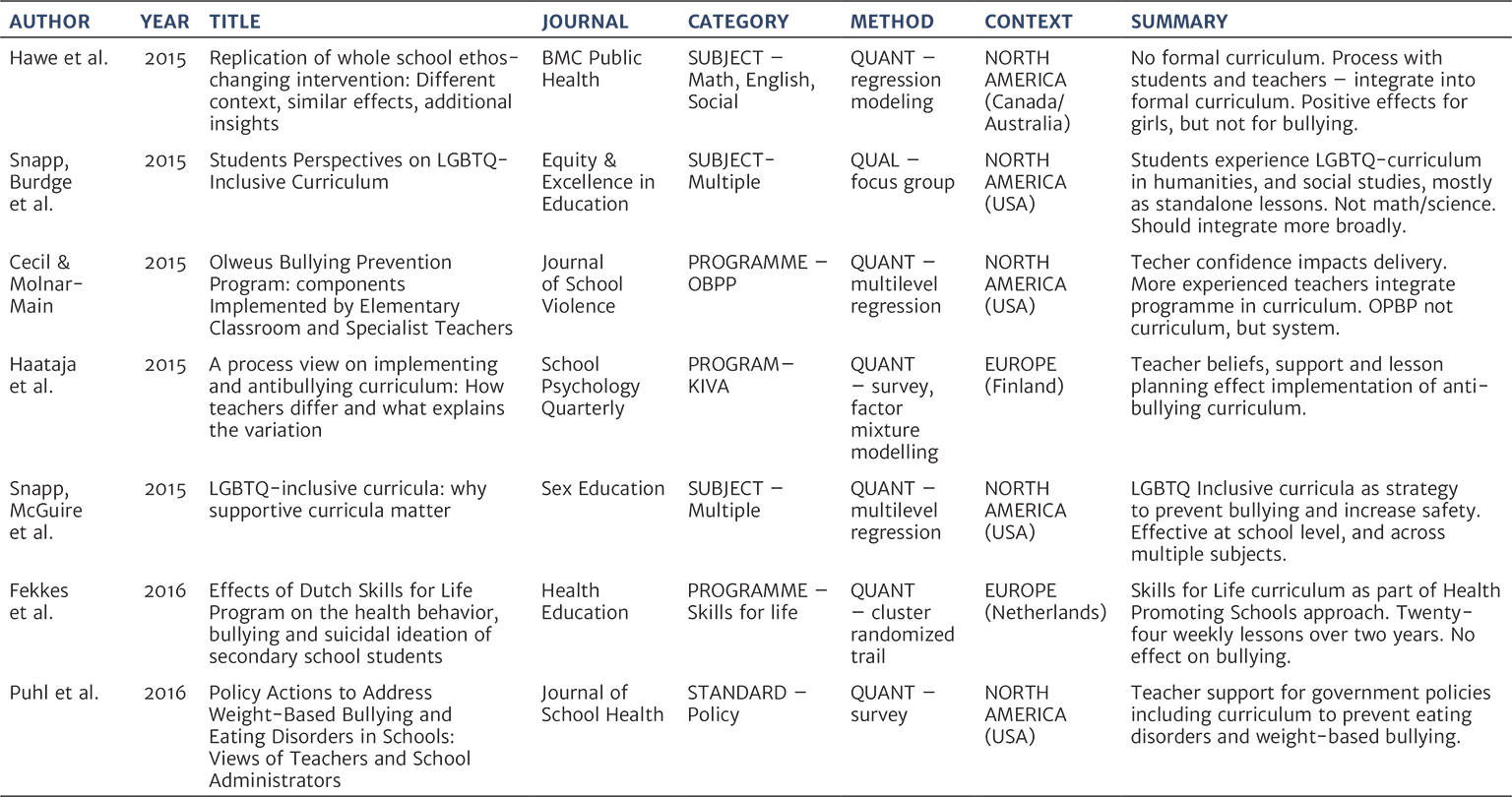

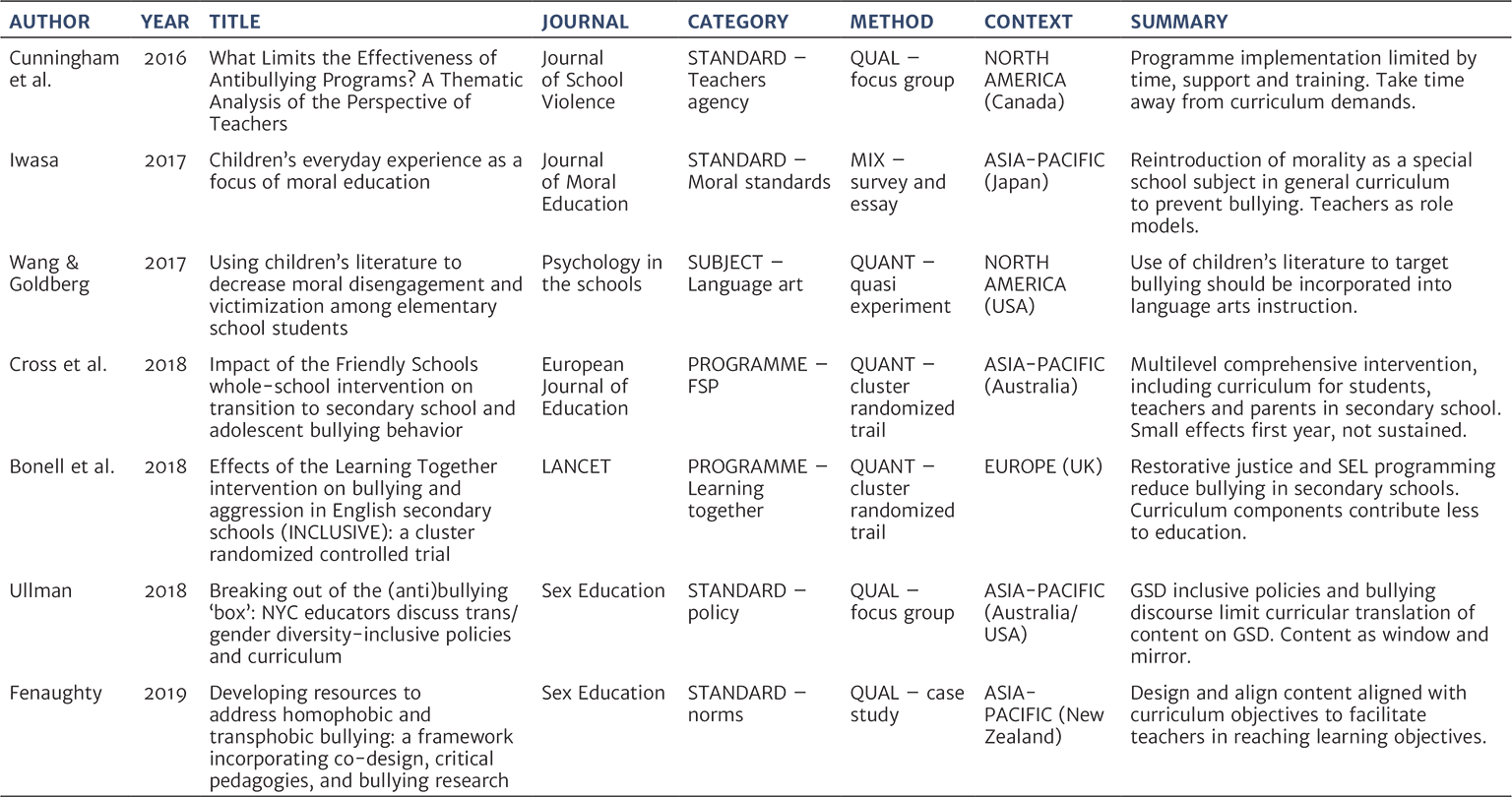

A total of 35 articles were reviewed in full text. Six articles were excluded for lack of relevance, leaving a corpus of 29 studies (see Appendix 1 for details) that were added to NVIVO 12 for further analysis and coding. Two of the articles investigating students’ experiences with LGBTQ-inclusive curricula in schools were written by the same author (Snapp, Burdge et al., 2015; Snapp, McGuire et al., 2015). Both articles were considered relevant and substantially different enough to warrant inclusion in the current study. This inclusion has contributed to a higher number of items from North America, and to a greater emphasis on LGBTQ-issues in the corpus, than would otherwise have been the case.

Based on the reading of systematic reviews, three main categories were used in the coding of articles. Studies addressing curriculum in anti-bullying programmes, including standalone and whole- school programmes are coded in the programme category. The subject category contains studies addressing bullying prevention as topics in school subjects and across different subjects. Finally, the standard category contains studies addressing curriculum through issues such as school norms, teacher conduct and national standards. In the following, I present my findings of curriculum understanding using these categories.

Finding curriculum understanding in bullying research

The programme category

The programme category consists of twelve studies, including investigations of eight standalone programme interventions and four whole-school programmes.

Standalone

Battey and colleagues (2013) studied the Bully Prevention Challenge Course using a curriculum of one full day of rope challenge exercises that ask students to address bullying behaviour. Researchers found that the intervention needed to be delivered by an external facilitator and that it proved hard to sustain for regular teachers. In the Take the Lead programme examined by Domino (2013), teachers were trained by external trainers for a minimum of six hours to deliver a curriculum designed to enhance students’ social learning during regular class periods. Fekkes et al. (2016) also found teachers were extensively trained in the principles and ideas of the Skills for Life curriculum to deliver 25 lessons over two school years.

Espelage and colleagues (2013) emphasised teacher delivery of weekly student lessons on social and emotional learning in the Second Step: Student Success Through Prevention programme. Lessons were designed to be highly interactive, incorporating small group discussions, dyadic exercises, whole-class instruction, and individual work. In the Steps to Respect programme, Low and associates (2010) found that student engagement with lessons was influenced by classroom ecology and teachers’ skills in both instruction and classroom management. Patchin and Hinduja (2010) also argued that programmes incorporated into the school curricula should include substantive instruction on cyberbullying.

Wurf (2012) found that the Shared Concern curriculum was less likely to have an impact when used in isolation, and it was more likely to have an impact in concert with other preventive components and used across the whole school. This contrasts with Renshaw and Jimerson (2012), who argue that while large-scale, multi-component programmes are likely to have a negative impact on school staff motivation, a new wave of bullying prevention programming emphasising teacher feasibility and local adaptation could increase staff support for interventions against bullying.

Whole school

Haataja et al. (2014) investigated differences in teacher delivery of the KiVA anti-bullying curriculum. The study found that teachers’ belief in the programme and time spent preparing for lessons influenced the quality of implementation of anti-bullying interventions. Bonell and colleagues (2018) found curriculum delivery to be one of the most time-consuming components of their programme, and, due to lack of fidelity, such components were less likely to contribute to a reduction in negative health outcomes. In a study of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program (OBPP), Cecil and Molnar-Main (2015) also found that, with experience, teachers become more skilled at integrating programme activities into their curriculum.

A Friendly Schools intervention on the transition to secondary school evaluated by Cross et al. (2018) found positive effects on rates of bullying in the first year, but the effects could not be sustained over time. Researchers argue that efforts to prevent bullying should engage more with students in co-design and leadership of future interventions.

Themes in the programme category

Taken together, the programme category is dominated by studies from North America that favour a quantitative assessment of bullying prevention.

In the programme category, understanding of curriculum can be described using three main themes. First, several studies emphasise teacher training for and student engagement with lessons on bullying (Cecil & Molnar-Main, 2015; Domino, 2013; Haataja et al., 2014; Low et al., 2014). It also discusses how teacher fidelity (Bonell et al., 2018; Cecil & Molnar-Main, 2015; Renshaw & Jimerson, 2012) and the scope of programming affect staff support. Finally, studies across both subcategories (Cross et al., 2018; Low et al., 2014) emphasise curriculum delivery as time consuming, calling for engagement with students to design new interventions.

The subject category

The subject category contains ten studies, including seven studies investigating bullying prevention in specific school subjects, and three studies related to outcomes across multiple subjects.

Single-subject

O’Connor and Graber (2014) found that physical education teachers supported a bullying climate by providing mixed information about social interactions, ignoring instances of bullying, and making inappropriate curricular choices in classes. Recognizing the risk of embarrassment in physical education classes, Gibbone and Manson (2010) argue that educators can contribute to school-wide prevention of bullying through character education and a positive classroom, school, and community climate. Kidger and colleagues (2009) found that both students and staff felt too little time was spent teaching about emotional health. Students also felt such issues should be addressed in other non-health-related curricula, such as English and drama, to avoid stigma.

Gourd & Gourd (2011) found the use of forum theatre in social studies provides students with an opportunity to experience democracy and reflect on cases of bullying. Schmidt (2010) found LGTBQ issues missing in national standards for social studies. This, she argued, reinforces heterosexual roles, limits gender and sexual imagination, and constrains student engagement with and questioning of curricula in school.

Wang and Goldberg (2017) found positive outcomes from the use of children’s literature to reduce bullying among elementary school students. The researchers argued that such approaches may support integration of bullying prevention into daily language arts instruction. Similarly, Mack (2012) argued that English teachers can address the problem of bullying by teaching about emotions through the study of literature, writing, drama, media, and language. Every literary text, she claims, can be read for social justice, and teaching argumentative writing could be used to offer an alternative to a polarising and dichotomous media culture.

Cross-subject

Snapp, Burdge et al. (2015) found that students could identify LGBTQ curricula, mainly in the social sciences, humanities, and health classes, while subjects such as math and science do not appear to integrate LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum in their lessons. Teachers in these subjects, the researchers claim, may benefit from instruction on making their lessons more LGBTQ-inclusive. In a related study, Snapp, McGuire et al. (2015) also found that inclusive curricula may heighten students’ awareness of bullying and safety, leading to more reports of bullying, but also had positive implications for safety at the school level.

Hawe and colleagues (2015) highlighted how the CORE intervention did not recommend a particular curriculum package or lesson plans but rather encouraged teachers to think about how to address issues in the teaching of math, English and social studies and to develop pedagogies to promote student well-being in their classes.

Themes in the subject category

Taken together, the subject category is influenced by qualitative studies of curriculum in a North American context. The category highlights three themes. The first involves the way formal curriculum frameworks can limit students’ perceptions of identity (Schmidt, 2010) but also encourage teachers to reflect on their teaching practices (O’Connor & Graber, 2014) and contribute to bullying prevention (Gibbone & Manson, 2010; Gourd & Gourd, 2011; Mack, 2012). The second involves the way some school subjects, such as math and science (Hawe et al., 2015; Kidger et al., 2009; Snapp, Burdge et al., 2015) are not being leveraged for bullying prevention. The third theme concerns the way teachers are encouraged to integrate (Hawe et al., 2015; Mack, 2012; Wang & Goldberg, 2017) bullying prevention in subject curricula.

The standard category

The standard category contains seven studies, including four exploring general issues of professional conduct, and three studies related to government policies. The studies are explored using the subcategories of professionalism and governance.

Professionalism

Bibou-Nakou and colleagues (2012) argue that teacher practices such as name-calling, favouritism, and scapegoating are considered bullying practices by students. Iwasa (2017) argued that moral growth cannot be transmitted to students by teachers, but that teachers need to engage in moral issues as learners striving to become positive role models for students.

Cunningham et al. (2016) showed that teachers found it difficult to implement separate measures against bullying, prompting them to modify anti-bullying programmes or implement components as time and curriculum allowed. Fenaughty (2019) found that working with teachers in a co-design process while emphasising curricular alignment in tune with teachers’ needs was particularly important for educators concerned about how and whether they should be teaching controversial issues.

Governance

Roland (2011) analysed two government interventions against bullying in Norway, finding that while bullying prevalence decreased during the first intervention (2002–2004), rates increased during the second intervention (2004–2008). He argued that implementation of a new national curriculum in 2006 may have had a negative impact on efforts to prevent bullying in schools.

Although the government, as compared to health workers, parents, and teachers, was seen as playing a minor role in prevention efforts, Puhl and colleagues (2016) found support among school staff for policies to address eating disorders in health curriculum as a means to prevent bullying.

Ullmann noted that curriculum is seen as “both a window and a mirror” (Ullman, 2018, p. 500), for students to learn about and reflect on gender and sexual diversity. She found that psychological explanations of bullying and confined government policies may constrain educators’ curricular translation and limit questioning of the heteronormative gender climate that contributes to marginalisation and bullying of non-binary youth.

Themes in the standard category

The standard category is the only category not dominated by studies from North America. Taken together, it can be understood as highlighting moral standards (Iwasa, 2017) and professional conduct (Bibou-Nakou et al., 2012), through professional autonomy (Ullman, 2018) seen as adaptation (Cunningham, Mapp et al., 2016) and curricular alignment (Fenaughty, 2019). The category not only highlights curriculum as government policy and standards for addressing issues (Puhl et al., 2016), but also as a source of competing priorities that may undermine efforts to prevent bullying in schools (Roland, 2011).

Discussing curriculum understanding in bullying research

The findings in this study shed light on how curriculum is understood in contemporary bullying research. While the concept of curriculum is seldom explicitly discussed, it is addressed in different ways across all categories. In the programme category, emphasis is mainly on curriculum as lesson content, whereas it is considered more as a framework in the subject category, and policy in the standard category. Views on teacher roles also differ, focusing on fidelity in the programme category, pedagogical integration in the subject category, and autonomy in the standard category. There also seem to be differences in how studies frame the research agenda going forward. In the programme category, new research to engage with students in efforts to prevent bullying is emphasised, while the subject category stresses research on subjects that have not been leveraged, and the standard category indicates a need to address competing priorities in policies. These findings reaffirm curriculum as a relevant concept in bullying research. They do not, however, make clear the theoretical understandings of curriculum employed by researchers in their work. In the following, I use my analytical framework to analyse such concepts, and to identify gaps that may constrain new insights into bullying prevention in schools.

Gaps in understanding of curriculum dimensions

Using curriculum dimensions (Dillon, 2009), the programme category, including whole-school approaches, can be seen as emphasising the what-dimension of curriculum as content on bullying in student lessons. This is clear in Espelage et al. (2013), who describe the Second Step curriculum as “content related to bullying, problem-solving skills, emotion management, and empathy” (p. 181). This is also evident in Haataja et al. (2014), who note that high implementers “covered approximately 85% of curriculum content per lesson” (p. 570). Espelage has also emphasised that “lessons are highly interactive, incorporating small group discussions and activities, dyadic exercises, whole-class instruction, and individual work” (Espelage et al., 2013, p. 181), indicating a concern with the how-dimension of curriculum as content delivery. In line with this, several studies emphasise teacher training (Cross et al., 2018; Haataja et al., 2014; Wurf, 2012), for example Haataja et al. (2014, p. 567) who describe a two-day pre-implementation training programme for teachers responsible for delivering lessons or for managing acute cases of bullying. Concern for curriculum delivery was also evident in the emphasis on implementation manuals (Battey & Ebbeck, 2013; Bonell et al., 2018; Domino, 2013; Fekkes et al., 2016), as demonstrated by (Cross et al., 2018) who described a six-hour group training session for pastoral care staff complemented by “a manual to guide whole-school implementation” (p. 501).

Lessons on bullying, teacher training, and programme manuals – the ‘what’ and ‘how’ dimensions of curriculum, are emphasised to a lesser degree in the subject category. Studies in this category instead emphasise teachers’ existing subject knowledge and pedagogical knowhow, as in Hawe et al. (2015), who note that researchers did not recommend a particular curriculum package or lesson plan but encouraged teachers to “think about how to address emotional literacy in the regular curriculum” (p. 3). Both the subject and standard categories then, are more concerned with questions of “why” and “who” in the curriculum. Mack (2012), for instance, argues that “emotional literacy has an important place in the English curriculum” (p. 18). Gourd and Gourd (2011) claim that the “social studies curriculum needs to help students to connect to all individuals with compassion and understanding” (p. 408). This is also evident across curriculum subjects, as illustrated by O’Connor and Graber (2014), who argue that we “must examine the extent to which our curricular choices are standards-based, developmentally appropriate, and focused on students’ development within each domain of learning” (p. 407), and by Schmidt (2010, p. 330) who insists that “the use of standards and themes to organize content and thinking is a normalizing process” (p. 330). The ‘who’-dimension of curriculum as governance is addressed by Ullman (2018), who calls for policies and leadership which explicitly invite teachers to share in a broad-based social agenda for their school communities, and laments “state and federal education departments’ current political distancing from specific LGBTQ inclusions at the policy and curriculum levels” (p. 507). Fenaughty positively stresses that “curriculum alignment has power to leverage offcial documentation to support the delivery of bullying prevention” (Fenaughty, 2019, p. 15), while Kidger and colleagues raise students’ concerns that “other lessons such as English and Drama, should also be acknowledged and supported in policy documents” (Kidger et al., 2009, p. 15).

As demonstrated above, bullying research engages with a broad range of curriculum dimensions across the different categories. While teachers’ existing pedagogical knowledge and the purpose of education are of greater concern in the subject and standard categories, the program category tends to emphasize content and delivery of a specific bullying curriculum. This constriction of curriculum knowledge within different categories of bullying research highlights a potential gap that may impede the development of a broader curriculum understanding in the field, and the use of such knowledge to prevent bullying in schools.

Gaps in understanding of curriculum narratives

Drawing on Elgström and Hellstenius (2011), bullying research can also be seen as conveying a curriculum narrative. Many studies (Cecil & Molnar-Main, 2015; Fekkes et al., 2016; Haataja et al., 2014; Wurf, 2012) in the programme category advocate an evidence-based approach to bullying prevention. Wurf (2012), for instance, has claimed that “whole-school approaches have been internationally recognised as the best evidence-based method to reduce school bullying” (Wurf, 2012, p. 139). Most studies in the programme category, and all in the whole-school subcategory, have employed quantitative designs to investigate the effects of interventions. Some studies have also emphasised expert knowledge and external facilitation (Battey & Ebbeck, 2013; Bonell et al., 2018), indicating a separation of expertise in bullying prevention from the expertise of teachers in school.

Accordingly, the programme category conveys an essentialist narrative of curriculum, emphasising bullying prevention through transmission of scientific knowledge by external experts. This is in contrast to the progressive narrative of the subject category, stressing the role of curriculum to address societal problems by recognizing that “individuals, families, and schools all exist within communities that may foster or hinder bullying” (O’Connor & Graber, 2014, p. 399) and how curriculum should be “promoting the use of critical questions about how inequality is institutionalized into society” (2010, p. 316). The progressive narrative is also evident in sentiments supporting the integration of bullying prevention into existing domains of knowledge (Gibbone & Manson, 2010; Gourd & Gourd, 2011; Snapp, Burdgeet al., 2015; Wang & Goldberg, 2017). This is expressed by Wang and Goldberg (2017), who stress the importance of integrating “bullying prevention into general classroom instruction to facilitate skill generalization”(p. 919), and Snapp, Burdge et al. (2015), who argue that “when schools integrate LGBTQ inclusive curriculum across multiple subjects, students feel safer and report more positive well-being than if inclusion only occurred in a couple of courses” (p. 261).

The reconstructive narrative, aiming at societal transformation through critical citizenship, is also more highly emphasised in the subject and standard categories. For instance, Fenaughty (2019), argued that a “norm-critical approach can be used to examine and critique the social norms” (p. 7), and that a curriculum focused on engaging young people in critical thinking, respect, stereotypes, diversity, and empathy is an important element in prevention. Similarly, Schmidt (2010) argues that “if a primary mission of schools is to prepare citizens, then it is important to query how students are prepared to take on the role of citizens in relation to the common good and the extension of rights” (p. 315).

In this section we have seen how bullying researchers convey a broad range of curriculum narratives across the different categories. These narratives are, however, unevenly distributed, with the subject and standards categories emphasizing progressive and reconstructive narratives, while the program category tends to favor the essentialist evidence-based narrative. This discussion highlights a potential gap in bullying research, where different categories of research operate from a singular narrative understanding of curriculum. This may impede the application of a broader curriculum understanding in bullying research and limit the use of plural narratives to prevent bullying in schools.

Gaps in an understanding of education systems

Finally, drawing on the critical realist distinction of open and closed systems (Bhaskar, 2008, 2016; Brown, 2009; Priestley, 2011; Tikly, 2015), the programme category, emphasising quantitative research and evidence-based approaches, can be seen as advocating an empiricist closed systems ontology of education. This is apparent in an emphasis on controlling teachers’ application of programming, as in Haataja et al. (2014), who insist that “fidelity of implementation is a critical factor” (p. 564) for successful prevention, Renshaw’s teacher fidelity checklists (2012), and Fekkes et al. (2016), who used logs to assess teacher fidelity in the Skills for Life programme. Such examples underline the assumption that factors can be successfully controlled to produce reliable outcomes across educational contexts—as within a closed system of education.

Contrary to this assumption, approaches in the subject and standard categories emphasise teacher professionalism and adaptation in bullying interventions. Notable in this regard are Hawe et al. (2015), who describe how teachers were “encouraged to adapt and embed these strategies into their teaching” (p. 2), and Cunningham, Mapp, et al. (2016), who cite educators’ perceptions that “failure to adapt the developmental level of anti-bullying activities limited their application across grades”(p. 467). This is in line with an ontological premise of education as an open system with multiple layers and interplay of agencies that produce inherently variable outcomes across different educational contexts.

Similarly, studies emphasising layers outside the school, as with Fenhaughy’s (2019) insistence on alignment with the national curriculum and Ullman’s (2018) call for greater engagement with LGBTQ issues at the policy level, indicate an understanding that these layers influence bullying in schools in an open educational system. Bullying research does recognize the need for “complementary components directed at different levels of the school organization” (Vreeman & Carroll, 2007, p. 86). It seems however, less inclined to engage in a discussion about the nature of the education systems in which it operates. Research in the program category seems to accentuate control and reproduction in a closed system ontology, while the subject and standard categories focus on teacher professionalism and outside influences more in line with education as an open system.

These findings indicate a gap between categories of bullying research that favor either closed or open system ontology. Such dichotomous positioning may exacerbate differences between different modes of bullying research and inhibit the development of a deeper ontological understanding of education systems. This in turn may constrict efforts to prevent bullying in schools in more theoretically coherent and collaborative ways.

Conclusions and implications

Building on the discussions above, curriculum understanding in bullying research can be illustrated in the following table. (Table 1: Curriculum understanding in bullying prevention)

| PROGRAMME | SUBJECT | STANDARD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sub-categories | Standalone

Whole school |

Single-subject

Cross-subject |

Professionalism

Governance |

| Themes | Lessons

Fidelity Student engagement |

Framework

Integration Subjects not leveraged |

Policy

Autonomy Competing priorities |

| Context | North America | North America | Asia-Pacific/Europe |

| Design | Quantitative | Qualitative | Qualitative |

| Dimension | (What) How | (What/How) Why | (What/Why) Who |

| Narrative | Essentialist | Progressive | Reconstructive |

| System | Closed | Open | Open |

The current review confirms curriculum as a relevant concept in bullying research as it connects the core activities of teaching and learning with efforts to prevent bullying in schools. Nevertheless, curriculum understanding is rarely discussed in bullying research. With the notable exception of Snapp et al., who declare “curriculum may be used to describe content in the form of lessons, diversity training, or programmes of study within the school context” (Snapp, Burdge et al., 2015, p. 261), none of the reviewed studies explicitly define their use of the term curriculum. This lack of conceptual clarity makes it difficult to assess how researchers understand curriculum in schools, and in their own research. It also makes it more difficult for researchers engaged with bullying and curriculum to work together. Using curriculum theory as an analytical framework, this article suggests that new insights can be gained by outlining understandings of curriculum in bullying research. From a bullying perspective, teaching and learning in schools may be seen as competing demands (Cunningham, Mapp et al., 2016) offsetting efforts to prevent bullying (Roland, 2011). From a curriculum perspective however, such juxtaposing seems misplaced, as schools are increasingly expected to work on both social and academic outcomes. In the review by Tancred et al. (2018) a push towards more integrated approaches to teaching and prevention in schools is evident. Researchers, however, also point out that such approaches need to be developed further. Instead of juxtaposing, would it not make more sense for scholars in bullying and curriculum research to collaborate on new strategies to prevent bullying and enhance learning in schools?

Findings from the current research also indicate that while the bullying field as a whole represents a broad curriculum understanding, such understanding seems constricted to different modes of bullying research, in the program, subject and standard categories. This compartmentalization of knowledge is analyzed here as gaps in understanding of curriculum dimensions, curriculum narratives and education systems ontology, and risks underutilizing insights from across the field and constricting the development of new and innovative ways to integrate bullying prevention on all levels of the curriculum. Building on the critical realist notion of immanent critique (Bhaskar, 2016, p. 3), the strong idea of the whole-school approach (Farrington & Ttofi, 2009; Rigby & Slee, 2008; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011; Vreeman & Carroll, 2007) Farrington & Ttofi, 2009; Rigby & Slee, 2008; Ttofi & Farrington, 2011; Vreeman & Carroll, 2007) can be seen as perpetuating a narrow understanding of curriculum that is counterproductive to bullying prevention. Several of the programmes investigated in this study (Bonell et al., 2018; Cecil & Molnar-Main, 2015; Cross et al., 2018; Haataja et al., 2014) subscribe to this approach, and typically include anti-bullying policies, student curriculum, staff training, and engagement with parents and community. Such programs, however, rarely include subject curriculum or curriculum standards as components in bullying prevention. Labelling efforts as “whole-school” while ignoring these central components of curriculum in schools is a red herring that may constrain the application of teachers’ pedagogical knowledge in bullying prevention. Rather than hailing the whole-school approach as a panacea, perhaps we should be asking, is there a hole in the whole-school approach? One way a curriculum perspective can add insight into bullying prevention is by insisting that curriculum knowledge should be more broadly included in the whole-school approach. This may liberate, rather than constrict, teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and enable more sustainable strategies to preventing bullying in schools.

A general implication of this study is that curriculum understanding should be more clearly addressed in bullying research. Further research is needed to identify how curriculum concepts are understood by researchers in the field, and how curriculum understanding may be leveraged to improve bullying prevention in schools. Researchers working on program development should be mindful of existing pedagogical knowledge in schools, and how curriculum understandings may be employed in a broader strategy to prevent bullying. Without such strategies bullying research may lose favor in schools that are increasingly called upon to deliver on curriculum demands, and inadvertently disconnect bullying prevention from the core activities of teaching and learning. Policymakers and funders of bullying research should encourage more collaboration within and across relevant fields to ensure a broad understanding of curriculum is put to work to tackle bullying in schools. New partnerships and strategies to align bullying prevention and curriculum development should also be explored. Such partnerships should be informed by multi-disciplinary longitudinal research and a deep ontological understanding of education as a complex layered system.

Finally, this study has particular relevance for research and policy in the Nordic context. As the cradle of bullying research (Heinemann, 1972; Olweus & Møller, 1975) Nordic countries have a long history of developing knowledge and measures to deal with bullying in schools. Nordic countries also share a common influence from curricular traditions (Karseth & Sivesind, 2010; Oftedal Telhaug et al., 2006) that emphasise teacher professionalism, pedagogical knowledge and social learning in schools. As such it is ideally suited to support innovations that can integrate bullying prevention with teaching and learning in schools. I agree with Thornberg and colleagues who posit that a pedagogical perspective on bullying “has to consider national and local school policies; school as an organization and as an institution; teachers as role models, their classroom management and efforts to influence students social and moral growth; and social processes in school classes and peer groups” (Thornberg, Baraldsnes, et al., 2018, p. 296). To this I would add, it should also consider curriculum as a core component of pedagogy and bullying prevention in schools. It is encouraging to see how Nordic scholars (Eriksen, 2018; Eriksen & Lyng, 2018; Horton, 2018; Lyng, 2018; Repo & Repo, 2016; Repo & Sajaniemi, 2015; Schott & Søndergaard, 2014; Søndergaard & Hansen, 2018; Thornberg, Wänström, et al., 2018; Thornberg et al., 2017) are increasingly addressing similar issues in bullying research. Many more such efforts should be welcomed, and more researchers working in the Nordic context should publish their work widely for international colleagues to read. Recently, revisions of the national curriculum in Norway (Norwegian Ministery of Education and Research, 2016) and Finland (Halinen, 2018) focusing on school culture and an integrative curriculum also indicate a shift toward a more holistic approach to bullying prevention at the policy level. Moving forward, these developments should inspire new research and collaborations that may light the way towards more systemic, systematic and sustainable ways of addressing bullying in schools.

Caveats and limitations

There are several limitations to this study. Firstly, the small number of articles included does not represent the full width, nor the depth of curriculum understanding in the field. A research design allowing for more studies and better differentiation across contexts may alter and add nuance to the findings discussed here. This is certainly pertinent with regards to the overrepresentation of quantitative studies from the North American context in this review. Secondly, the conclusion drawn indicating a constricted understanding of curriculum in bullying research does not necessarily mean that researchers are constricted in their understanding of curriculum. As I have only included peer reviewed journal articles in this study, there is a good chance these findings stem, not from a lack of curriculum understanding, but from a lack of space in the format I have chosen to review. Including books, reports and other scholarly works may provide a broader picture of how scholars understand curriculum in their work and add nuance to the picture painted here. There is reason to believe that scholars understand, and are already addressing these issues at the practice level. Bonell et al. (2018), for instance, argue for “single coherent interventions rather than overburdening busy schools with multiple interventions” (p. 2452). After recognizing the constraints on teachers’ time, Cross et al. (2018) adapted their programme in line with teachers’ feedback. Finally, the biases associated with single authorship and a theoretical positioning in critical realism should also be considered, as these factors have undoubtedly impacted on both the selection and coding of articles. With these limitations in mind the claims made here should be viewed not as claims of fact, but rather as arguments to stimulate debate on the role of curriculum in bullying research.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments, and Helle Rabøl Hansen, Paul Horton and Selma Therese Lyng for their inspiring inputs on earlier versions of this article.

REFERENCES

- Battey, G. J. & Ebbeck, V. (2013). A qualitative exploration of an experiential education bully prevention curriculum. Journal of Experiential Education, 36(3), 203–217.

- Bhaskar, R. (2008). Dialectic: the pulse of freedom. London: Routledge.

- Bhaskar, R. (2016). Enlightened common sense: The philosophy of critical realism. London: Routledge.

- Bibou-Nakou, I., Tsiantis, J., Assimopoulos, H. et al. (2012). School factors related to bullying: A qualitative study of early adolescent students. Social psychology of education, 15(2), 125–145.

- Bonell, C., Allen, E., Warren, E. et al. (2018). Effects of the Learning Together intervention on bullying and aggression in English secondary schools (INCLUSIVE): A cluster randomised controlled trial. The Lancet, 392(10163), 2452–2464.

- Brown, G. (2009). The ontological turn in education: The place of the learning environment. Journal of Critical Realism, 8(1), 5–34.

- Cassidy, W., Faucher, C. & Jackson, M. (2013). Cyberbullying among youth: A comprehensive review of current international research and its implications and application to policy and practice. School Psychology International, 34(6), 575–612.

- Cecil, H., & Molnar-Main, S. (2015). Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: Components implemented by elementary classroom and specialist teachers. Journal of school violence, 14(4), 335–362.

- Cohen, L., Lawrence, M. & Morrison, K. (2018). Research methods in education, 8 ed. London: Routledge.

- Cross, D., Shaw, T., Epstein, M. et al. (2018). Impact of the Friendly Schools whole-school intervention on transition to secondary school and adolescent bullying behaviour. European Journal of Education, 53(4), 495–513.

- Cunningham, C. E., Mapp, C., Rimas, H. et al. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of students. Psychology of Violence, 6(4), 596.

- Cunningham, C. E., Rimas, H., Mielko, S. et al. (2016). What limits the effectiveness of antibullying programs? A thematic analysis of the perspective of teachers. Journal of School Violence, 15(4), 460–482.

- Dillon, J. T. (2009). The questions of curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 41(3), 343–359.

- Domino, M. (2013). Measuring the impact of an alternative approach to school bullying. Journal of School Health, 83(6), 430–437.

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B. et al. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432.

- Elgström, O. & Hellstenius, M. (2011). Curriculum debate and policy change. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 43(6), 717–738.

- Eriksen, I. M. (2018). The power of the word: Students’ and school staff’s use of the established bullying definition. Educational Research, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2018.1454263

- Eriksen, I. M. & Lyng, S. T. (2018). Relational aggression among boys: Blind spots and hidden dramas. Gender and Education, 30(3), 396–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2016.1214691

- Espelage, D. L., Low, S., Polanin, J. R. et al. (2013). The impact of a middle school program to reduce aggression, victimization, and sexual violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 53(2), 180–186.

- Farrington, D. P. & Ttofi, M. M. (2009). School-based programs to reduce bullying and victimization. The Campbell Collaboration, 6, 1–149.

- Fekkes, M., van de Sande, M., Gravesteijn, J. et al. (2016). Effects of the Dutch skills for life program on the health behavior, bullying, and suicidal ideation of secondary school students. Health Education, 116(1), 2–15.

- Fenaughty, J. (2019). Developing resources to address homophobic and transphobic bullying: A framework incorporating co-design, critical pedagogies, and bullying research. Sex Education, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2019.1579707

- Fox, B. H., Farrington, D. P. & Ttofi, M. M. (2012). Successful bullying prevention programs: Influence of research design, implementation features, and program components. International Journal of Conflict and Violence (IJCV), 6(2), 273–282.

- Gibbone, A. & Manson, M. (2010). Bullying: Proactive physical educators’ contribution to school-wide prevention. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 81(7), 20–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/07303084.2010.10598504

- Gourd, K. M. & Gourd, T. Y. (2011). Enacting democracy: Using forum theatre to confront bullying. Equity & Excellence in Education, 44(3), 403–419.

- Haataja, A., Voeten, M., Boulton, A. J. et al. (2014). The KiVa antibullying curriculum and outcome: Does fidelity matter? Journal of school psychology, 52(5), 479–493.

- Halinen, I. (2018). The new educational curriculum in Finland. Improving the quality of childhood in Europe, 75–89.

- Hawe, P., Bond, L., Ghali, L. M. et al. (2015). Replication of a whole school ethos-changing intervention: Different context, similar effects, additional insights. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 265.

- Heckman, J. J. & Kautz, T. (2013). Fostering and measuring skills: Interventions that improve character and cognition. Retrieved from https://www.nber.org/papers/w19656

- Heinemann, P.-P. (1972). Mobbning. Gruppvåld bland barn och vuxna. Stockholm: Natur och Kultur.

- Helgeland, A. & Lund, I. (2017). Children’s voices on bullying in kindergarten. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(1), 133–141.

- Horton, P. (2018). Towards a critical educational perspective on school bullying. Nordic Studies in Education, 38(04), 302–318.

- Iwasa, N. (2017). Children’s everyday experience as a focus of moral education. Journal of Moral Education, 46(1), 58–68.

- Juul, K. D. (1989). Some common and unique features of special education in the Nordic countries. International Journal of Special Education, 4(1), 85–96.

- Karseth, B. & Sivesind, K. (2010). Conceptualising curriculum knowledge within and beyond the national context. European Journal of Education, 45(1), 103–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-3435.2009.01418.x

- Kidger, J., Donovan, J. L., Biddle, L. et al. (2009). Supporting adolescent emotional health in schools: A mixed methods study of student and staff views in England. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 403.

- Limber, S. P., Olweus, D., Wang, W. et al. (2018). Evaluation of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program: A large scale study of US students in grades 3–11. Journal of School Psychology, 69, 56–72.

- Low, S., Van Ryzin, M. J., Brown, E. C. et al. (2014). Engagement matters: Lessons from assessing classroom implementation of steps to respect: A bullying prevention program over a one-year period. Prevention Science, 15(2), 165–176.

- Lyng, S. T. (2018). The social production of bullying: Expanding the repertoire of approaches to group dynamics. Children & Society. https://doi.org/10.1111/chso.12281

- Mack, N. (2012). EJ in focus: Bullying reconsidered: Educating for emotional literacy. The English Journal, 101(6), 18–25.

- Mølstad, C. E. & Hansén, S.-E. (2013). The curriculum as a governing instrument – a comparative study of Finland and Norway. Education Inquiry, 4(4). https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i4.23219

- Norwegian Ministery of Education and Research. (2016). St.meld nr. 28 (2015–2016), Fag – Fordypning – Forståelse. En fornyelse av kunnskapsløftet. [Subjects – Emersion – Understanding. A renewal of knowledge promotion] Oslo: Norwegian Ministery of Education and Research. Retrieved from https://www.regjeringen.no/contentassets/e8e1f41732ca4a64b003fca213ae663b/no/pdfs/stm201520160028000dddpdfs.pdf

- O’Connor, J. A. & Graber, K. C. (2014). Sixth-grade physical education: An acculturation of bullying and fear. Research Quarterly for Exercise and Sport, 85(3), 398–408.

- OECD. (2015). Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills (9264226141). Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/education/skills-for-social-progress-9789264226159-en.htm

- OECD. (2018). The future of education and skills – Education 2030. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030%20Position%20Paper%20(05.04.2018).pdf

- Oftedal Telhaug, A., Asbjørn Mediås, O. & Aasen, P. (2006). The Nordic model in education: Education as part of the political system in the last 50 years. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 50(3), 245–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313830600743274

- Olweus, D. & Møller, H. (1975). Hakkekyllinger og skolebøller: Forskning om skolemobning:(Omsl.: Kjeld Wiedemann). Gyldendal.

- Patchin, J. W. & Hinduja, S. (2010). Cyberbullying and self-esteem. Journal of School Health, 80(12), 614–621.

- Pettersson, D. (2014). Three narratives: National interpretations of PISA. Knowledge Cultures, 2(4), 172–191.

- Pettersson, D., Prøitz, T. S. & Forsberg, E. (2017). From role models to nations in need of advice: Norway and Sweden under the OECD’s magnifying glass. Journal of Education Policy, 32(6), 721–744.

- Pinar, W. F., Reynolds, W. M., Slattery, P. et al. (1995). Chapter 15: Understanding curriculum: A postscript for the next generation. Counterpoints, 17, 847–868.

- Priestley, M. (2011). Whatever happened to curriculum theory? Critical realism and curriculum change. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 19(2), 221–237.

- Puhl, R. M., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Bryn Austin, S. et al. (2016). Policy actions to address weight-based bullying and eating disorders in schools: Views of teachers and school administrators. Journal of School Health, 86(7), 507–515.

- Renshaw, T. L. & Jimerson, S. R. (2012). Enhancing student attitudes via a brief, universal-level bullying prevention curriculum. School Mental Health, 4(2), 115–128.

- Repo, L. & Repo, J. (2016). Integrating bullying prevention in early childhood education pedagogy. Contemporary perspectives on research on bullying and victimization in early childhood education, 273–294.

- Repo, L. & Sajaniemi, N. (2015). Prevention of bullying in early educational settings: Pedagogical and organisational factors related to bullying. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 23(4), 461–475.

- Rigby, K. & Slee, P. (2008). Interventions to reduce bullying. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health, 20(2), 165–184.

- Roland, E. (2011). The broken curve: Effects of the Norwegian manifesto against bullying. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 35(5), 383–388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025411407454

- Rose, C. A., Espelage, D. L. & Monda-Amaya, L. E. (2009). Bullying and victimisation rates among students in general and special education: A comparative analysis. Educational Psychology, 29(7), 761–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410903254864

- Schmidt, S. J. (2010). Queering social studies: The role of social studies in normalizing citizens and sexuality in the common good. Theory & Research in Social Education, 38(3), 314–335.

- Schott, R. M. & Søndergaard, D. M. (2014). School bullying: new theories in context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Snapp, S. D., Burdge, H., Licona, A. C. et al. (2015). Students’ perspectives on LGBTQ-inclusive curriculum. Equity & Excellence in Education, 48(2), 249–265.

- Snapp, S. D., McGuire, J. K., Sinclair, K. O. et al. (2015). LGBTQ-inclusive curricula: Why supportive curricula matter. Sex Education, 15(6), 580–596.

- Suri, H. (2013). Epistemological pluralism in research synthesis methods. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 26(7), 889–911.

- Søndergaard, D. M. (2014). From technically standardised interventions to analytically informed, multi-perspective intervention strategies. In R. M. S. Schott & D. Marie (Eds.), School bullying: New theories in context (pp. 389–404). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Søndergaard, D. M. & Hansen, H. R. (2018). Bullying, social exclusion anxiety and longing for belonging. Nordic Studies in Education, 38(04), 319–336.

- Tancred, T., Paparini, S., Melendez-Torres, G. et al. (2018). Interventions integrating health and academic interventions to prevent substance use and violence: A systematic review and synthesis of process evaluations. Systematic Reviews, 7(227), 1–16.

- Thornberg, R. (2011). ‘She’s weird!’ – the social cconstruction of bullying in school: A review of qualitative research. Children & Society, 25(4), 258–267. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2011.00374.x

- Thornberg, R., Baraldsnes, D. & Saeverot, H. (2018). Editorial: In search of a pedagogical perspective on school bullying. Nordic Studies in Education, 38(04), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1891-2018-04-01

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L. & Jungert, T. (2018). Authoritative classroom climate and its relations to bullying victimization and bystander behaviors. School Psychology International, 0143034318809762.

- Thornberg, R., Wänström, L. & Pozzoli, T. (2017). Peer victimisation and its relation to class relational climate and class moral disengagement among school children. Educational Psychology, 37(5), 524–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2016.1150423

- Tikly, L. (2015). What works, for whom, and in what circumstances? Towards a critical realist understanding of learning in international and comparative education. International Journal of Educational Development, 40, 237–249.

- Ttofi, M. M. & Farrington, D. P. (2011). Effectiveness of school-based programs to reduce bullying: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 7(1), 27–56.

- Ullman, J. (2018). Breaking out of the (anti) bullying ‘box’: NYC educators discuss trans/gender diversity-inclusive policies and curriculum. Sex Education, 18(5), 495–510.

- Vreeman, R. C. & Carroll, A. E. (2007). A systematic review of school-based interventions to prevent bullying. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine, 161(1), 78–88.

- Wang, C. & Goldberg, T. S. (2017). Using children’s literature to decrease moral disengagement and victimization among elementary school students. Psychology in the Schools, 54(9), 918–931.

- Westbury, I. (1998). Didaktik and curriculum studies. Didaktik and/or curriculum: An international dialogue, 47–48.

- Wurf, G. (2012). High school anti-vullying interventions: An evaluation of curriculum approaches and the method of shared concern in four Hong Kong international schools. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22(1), 139–149. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.2

- Young, M. (2013). Overcoming the crisis in curriculum theory: A knowledge-based approach. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 45(2), 101–118.

Appendix