Introduction

This article contributes to the numerical representation of the empirical outcome of the work of various educational traditions and practices in several European countries. The tasks of both teacher education and schools (teacher educators and teachers) are guided by distinct educational frameworks and societal settings. In Central and Northern Europe, the Didaktik tradition is dominant in framing teacher education, while the curriculum tradition prevails in Anglophone teacher training. In both cases, guidance for pedagogical decision-making based upon the two traditions is at the heart of the development of teachers’ pedagogical thinking. Accordingly, outcomes of teachers’ enactment work are then traceable over a lifespan and might differ according to varying educational inputs and processes. Although we take a comparative approach, this is limited by the fact that our analyses are based on teacher education.

Through the development of this non-conventional approach, we address a few limited dimensions of the rich concept of Bildung by reanalysing quantitative data collected regularly through the European Social Survey (ESS). Like other quantitative studies in education, we see the dataset and associated variables as social constructs. Through the development of certain quantitative proxies for a limited set of dimensions of Bildung – relying on theoretical conceptions developed within the Bildung-based Didaktik tradition – we aim to uncover what such an operationalisation reveals. We acknowledge that what we are doing is not common, because the Bildung tradition developed from philosophical and hermeneutical epistemological positions that understandably and traditionally have relied on inherent qualitative approaches as modes of research. However, in contrast to traditional approaches, we offer a new understanding of Bildung by addressing this rich and, at times, complex tradition quantitatively.

Based on the above arguments, we proceed in the following section with a presentation of our understanding of Bildung and the concept of literacy before moving on to a discussion of Aristotelian value sets as the basis of our operationalisation, which is strongly situated in the work of Wolfgang Klafki. We also elaborate on an empirical construction of the ESS. The state of art in Bildung-related quantitative research is presented in the two subsequent sections.

Aristotelian understanding of human potential and human flourishing

On Bildung and literacy

While the discourse on education and curriculum in Europe has been mostly dominated by educational buzzwords such as learning outcomes, skills-based education or competency-based curricula (to name a few), in this article we turn to an older and arguably elusive German concept – Bildung – in an attempt to quantify and compare it as an outcome of educational culture across nine European countries. Bildung is central in the Didaktik tradition of education, and it is the dominant guiding framework in formal and informal education in Continental and Nordic Europe (Sjöström et al., 2017). While considered impossible to translate into English, the German concept Bildung is a noun meaning something like ‘being educated, educatedness’ (Hopmann, 2007). It also carries connotations of the word bilden – ‘to form, to shape’. Other terms used to translate the term Bildung include ‘formation’, ‘self-formation’, ‘cultivation’, ‘self-development’ and ‘cultural process’ (Siljander & Sutinen, 2012). In the classical sense, Bildung encompasses the contents of assisting individuals to achieve their self-determination by developing and using their reason without the guidance of others and acquiring the cultural objects of the world into which those individuals are born and in which they are situated (Klafki, 2000; Hudson, 2003). Further, Bildung, from a Humboldtian perspective, is both a process and outcome in developing a person through education (Schneuwly & Vollmer, 2018). As a verbal noun, it is used either transitively or intransitively (Werler, 2010). Historically, Bildung became part of teacher education and school culture in the wake of the reorganisation of the German educational system (Jeismann & Lundgreen, 1987). Several authors have shown that the concept of Bildung has been highly relevant as a framework for both school and teacher education development in both Central and Northern Europe (Kansanen, 1999; Werler, 2004; Hudson, 2007; Pantić & Wubbels, 2012).

In the Anglophone sphere, the curriculum tradition is dominant, and primarily based on the instrumental concept of providing various types of literacy, which on the surface is a ‘straightforward’ basic educational offer. The concept bears signs of utilitarianism, because it emphasises the teaching of useful knowledge and the development of competences as promoted by the tradition’s dominant ideology of social efficiency (Deng & Luke, 2008; Horlacher, 2017a; Tahirsylaj, 2017). It is particularly important here that neither the process nor the outcome is emphasised. Of importance is the psychometrically measurable output in the form of test scores, learning outcomes and/or competences (Ravitch, 2010). Literacy describes desired and quantifiable learning results (Werler, 2010).

Currently, Bildung is often collected in a routine manner in surveys and analysed using statistical models (e.g. Bildung is operationalised as years of formal education, parents’ education degree (Kunter et al., 2014; Weinert et al., 2013), often without prior theoretical reflection. This can be shown by the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS), which quantifies Bildung as achievement (Bos et al., 2013). In our view, two approaches are currently pursued in quantitative research. Socio-structural operationalisation sees Bildung as a dependent variable. Typical indicators are education expenditure, school attendance rates and the proportion of the population with a university degree or the average length of education in a country (e.g. TIMSS). The operationalisation typical of human capital approaches sees Bildung as an independent variable (e.g. the Programme for the International Student Assessment [PISA]). Because the knowledge and skills of a country’s population are not expressed through their schooling alone, it has recently become common practice to use the cognitive performance of the population, measured by psychometric approaches, as a measure of their Bildung (e.g. Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies [PIAAC].

Summarising statements made over time, Tröhler (2011) documents that several authors (including himself) have judged that it is not possible to measure Bildung. A recent publication on ‘Bildung and Growth’ (Siljander & Sutinen, 2012) does not bring up the issue of operationalisation and the measurement of Bildung. Even Horlacher (2017b), presenting German discourse on Bildung between the 18th and 21st centuries, avoids dealing with the topic. The authors of these texts possibly assume that any epistemological category (here Bildung) must be covered by a similar epistemological capacity (here: ability to measure Bildung). In other words, the authors argue that human beings do not have the epistemological capacity to investigate Bildung quantitatively. To a certain extent, we agree with this idea. If the concept of Bildung describes both a holistic outcome and an educational process at the same time, then it is not accessible to human understanding because of its ambiguity.

However, we assume that outcome perspectives of Bildung can be examined at a given moment in time. The central idea of our efforts is to create a mathematical representation of Bildung as an outcome. For our project, this means that we understand Bildung as a scale-based measurable quantity, where items function as indicators for Bildung as an outcome, representing people’s education induced values and attitudes.

To achieve this, we consider it necessary to develop a proxy for Bildung (as a holistic outcome). The basic idea of such a proxy construction is that all education systems enact and practice education values as manifested by teachers’ work. Through that work/practice they create people’s continual value sets. Hence, even as qualitative expressions these value sets are accessible for quantitative measuring. To do so, we rely on a strong theoretical foundation developed primarily since the German Enlightenment in the 18th century and the modern psychology of ethics and values.

To this end, the article is as much qualitative as it is quantitative in nature. This means that we acknowledge that some outcome related dimensions of Bildung have measurable qualities (such as values and attitudes) in a quantitative way. In the following, we argue that it is possible to deconstruct outcome related aspects of Bildung into measurable variables relying on the work of the German pedagogue Wolfgang Klafki and the psychologist Shalom Schwartz, who both measured social values and attitudes. Both build their theories on Aristotelian ethics and focus their work on the development or measurement of human values.

In our research model, we follow the Aristotelian approach that human potential and flourishing need human concepts of upbringing and education framed by political institutions. The advantage of this approach is that it allows for multiple rationalities and attentiveness to the individual, as well as to the community.

Next, we outline the basic outcome related aspects of the Klafkian concept of Bildung. In doing so, we limit the scope of this article and do not address people’s familiarity with epoch-typic key problems and their knowledge set regarding the multi-dimensionality of human life conditions (emotions, aesthetics, etc.).

The use of Klafki for our empirical endeavour is applicable because he views Bildung, in line with Aristotelian values (Aristotle, 1987) as the capability for self-determination, co-determination and solidarity (Klafki, 1998). This implies an operationalisation of theoretical constructs into measurable qualities relying on empirical and randomly collected data and following quantitative approaches.

Klafki explains that the self-determined person is in a position that allows her or him ‘to make independent responsible decisions about her or his individual relationships and interpretations of an interpersonal, vocational, ethical or religious nature’ (Klafki, 1998, p. 314). Second, he elaborates on co-determination. He stresses that, to realise co-determination, all members of a society must have the right to but also have to be enabled to ‘contribute together with others to the cultural, economic, social and political development of the community’ (Klafki, 1998, p. 314). In short, Klafki writes about individuals’ real participation regarding socially and individually significant issues. Finally, he points out that only the person’s ability to act in solidarity allows her or him to live a self- and co-determined life. Solidarity, for Klafki, is not only the recognition of equal rights but also the ‘active support for those whose opportunities for self-determination and co-determination are limited or non-existent due to social conditions, lack of privilege, political restrictions or oppression’ (Klafki, 1998, p. 314). In the following section we elaborate on the empirical construction and application of Schwartz’s approach that also encompasses the Klafkian value set of self-determination, co-determination and solidarity.

Studying human values

Amongst other things, the ESS started in 2002 to study the development of human values (Jowell et al., 2007). It operationalises Schwartz‘s value theory (1992) with representative and comparable population surveys across twenty European countries. Schwartz argued for universals in the content and the structure of individual values. It is measured by 10 distinct values and 40 items. Already in 1973 Rokeach (1973) showed that a person’s value system is stable over time, which is supported by research concerned with value change in society (e.g. Inglehart & Baker, 2000; Inglehart & Welzel, 2005). Further, a study has shown that teacher education does have an impact on value change (Hofmann-Towfigh, 2007). However, there are no published articles known to the authors that have investigated the change in student/population values in relation to values provided by distinct curriculum cultures and their enactment over time.

Against the backdrop of the project’s problems, we conducted a literature search (limited to peer reviewed scientific journals). For this purpose, the Web of Science, Scopus and Academic Search Elite databases were queried. Two questions were examined. First of all, the question of how values were studied using ESS data. Second, the question of how the human value scale is studied. The query resulted in 12 papers falling into two categories. The research primarily follows a policy approach, and methodological studies form a broad category. The studies falling into the first category examined political questions on the broadest level. Researchers have asked what factors have an impact on people’s values. Alternatively, they approach the question the other way around: how do values affect an external variable like well-being, democracy, religiosity or political attitudes (Lefter et al., 2010; Iluţ & Nistor, 2011; Kulin & Seymer, 2014; Carratalà Puertas & Frances Garcia, 2017; Reeskens & Vandecasteele, 2017; Morrison & Weckroth, 2018)? Studies related to this category compared various cohorts, either on the national or international comparative level. Typically, the studies compared certain age groups or use the entire (national) data set. The studies apply multi-group structural equation modelling. However, the methodological studies were concerned with methodological problems, as well as with questions about the quality of the data sets (Davidov & De Beuckelaer, 2010; Bilsky et al., 2011; Cieciuch & Davidov 2012; Saris et al., 2012). The studies were concerned about testing for the comparability of human values across countries and time. Further, studies have investigated the question of the intercultural transfer of knowledge and scales. The researchers used complex test methods to investigate these questions. Lastly, our search shows that no prior papers have used ESS human values variables for secondary analyses as proxies for exploring educational questions.

In search of dimensions of Bildung: A quantitative approach

In this section we discuss if – and how – the measurement of aspects of Bildung as an outcome of a curriculum and education culture is possible. To understand the current use and/or operationalisation of Bildung as an outcome in the research literature, we performed a database query, including Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC, EBSCO, Google Scholar and Pedocs.de covering German-speaking countries. All databases (title, abstract and keyword register) were searched for the search terms: ‘Bildung AND quantitative’, ‘Bildung AND qualitative’ and ‘Bildung AND operationalisation’ in both English and German. Surprisingly, the application of the search string ‘Bildung AND operationalisation’ did not produce useful results. The Scopus database query resulted in 134 documents containing the search terms ‘Bildung AND quantitative’. A closer view revealed that entries were primarily linked to German texts relating to disciplinary research in the sciences (124) and social sciences, including education (10). Out of those 10 studies, one was loosely coupled to Bildung and its quantification. Frost and Brockman (2014) discussed the equation of performance measurement with Bildung within German universities. Another 57 texts were of a qualitative character, where 24 fell into the area of social sciences and education.

The Web of Science database query resulted in 609 documents relating to the search terms. However, it was not possible to characterise even one of the entries as quantitative. Thirteen studies could be labelled qualitative. All other studies could be labelled as conceptual studies. The query revealed that the vast majority of the articles were of Anglo-American (110 US, 43 England, 5 Scotland and 4 Ireland), German (119), and Scandinavian origin (74, where 36 Norway, 22 Sweden and 16 Denmark). The same search carried out for the ERIC database resulted in 234 records linked to Bildung. Three of them were clearly labelled as qualitative studies and none as quantitative.

A negative picture emerges with regard to the Google Scholar query. Limiting the search string to ‘Bildung AND quantitative’ (limited to title and English language), produced no results. Applying the search string ‘Bildung AND qualitative’ resulted in one hit. The query of the German database Pedocs.de regarding the keyword combination ‘Bildung AND operationalisation’, ‘Bildung AND qualitative’, ‘Bildung AND quantitative’ did not yield any results.

Typically, the searches revealed that researchers have primarily published conceptual studies that discuss various aspects of the Bildung concept. The research has focused on processes of meaning making in groups and in individuals. These findings reflect that the Bildung concept emerged in a humanist tradition and stands out as a normative dimension of philosophical hermeneutics.

Research questions, data and methods

The present study uses data from the European Social Survey (ESS), which has collected data through random sampling in 36 European countries every two years since 2002. The following two main research questions are addressed: How do Didaktik and curriculum countries compare in terms of self-determination, co-determination and solidarity, as well as Bildung across ESS rounds? What are the factors associated with the Bildung proxy across participating countries in the study? For the first question, our hypothesis is that Didaktik countries will show higher means of Bildung proxy and its associated variables than curriculum countries in our study. The second question is exploratory in nature, and a number of independent variables are tested for association with the Bildung proxy. The survey is iterative and all the data from all eight ESS rounds from 2002 to 2016 are publicly available for researchers for secondary data analyses. The ESS survey covers the following topics: media and social trust; politics; subjective well-being, social exclusion, religion, national and ethnic identity; climate change; welfare attitudes; gender, year of birth and household grid; socio-demographic and human values. In this study, the variables under the human values domain were used to generate proxies for our concepts of interest, namely self-determination, co-determination and solidarity. Responses were originally coded as ‘Not like me at all’ to ‘Very much like me’ in questions such as ‘how important is it for you to make your own decisions and be free’, which after recoding was converted to a 0–4 scale, where 0 is ‘Not like me at all’ & ‘Not like me’ and 4 represents ‘Very much like me’. Stata software was used to conduct the analyses. ESS collects representative data in face-to-face interviews from about 2,000 respondents aged 15 years and older per country, and our final sample from nine countries from all eight ESS rounds had responses from a total of 138,472 respondents. Hence, the respondents hold values that have been moulded and created through their encounters and experiences with a specific educational practice.

The Bildung-proxy construction

As noted in previous sections, our operationalisation of the proxies for Bildung and its three associated concepts follows Klafki’s definition of three Bildung-related dimensions relying on ESS data. Out of many perspectives on Bildung, such as a classical understanding of Bildung from the German Enlightenment, the critical Bildung developed by Klafki and other postmodern views on Bildung, we have developed a straightforward model summarising and generalising previous discussions from the German-speaking research landscape.

Argumentatively, any educational practice influences and reflects the values of a society. Firstly, schools and teachers along with families, the media and peer groups are a major influence on the development of values in young people, and thus in society. Secondly, schools and teachers reflect and embody the values of society. In other words, education systems develop due to their social and cultural origins in ‘constitutional mind-sets’ (Hopmann, 2008, p. 425). These mind-sets ultimately determine what content and teaching practices are considered important in a school system and central and significant for the future.

In the present article, the central idea is that the formation of people’s values takes place at school. This is because teachers enact the values of the culture sphere that teacher education specifically and the education system in general rests upon. The core claim of the proxy construction is that teachers’ practice is framed and guided by the concept of Bildung (i.e. a value set). Primarily, student teachers and pupils encounter the concept of Bildung through their education, while it also frames their identity and schools’ culture. If student teachers and pupils are not exposed to teaching practices that are based on Bildung then a different value set is expected. It is thus reasonable to assume that these values must be detectable in people’s value mind-sets. To clarify this hypothesis, differences in comparison to other education systems must be investigated, and it seems worthwhile to compare human values reported by the ESS (Jowell et al., 2007). The applied concept is based on Schwartz’s theory of Basic Human Values (Schwartz, 1992). The studied values are defined as ‘desirable, trans-situational goals, varying in importance, that serve as guiding principles in the life of a person or other social entity’ (Schwartz, 1994, p. 21). The ESS questionnaire regarding human values builds upon a circumplex model of ten values (Schwartz & Huismans, 1995). The values measured by the ESS are security, conformity, tradition, benevolence, universalism, self-direction, hedonism, achievement and power (Schwartz, 2003).

In this study, we operationalised the research questions by applying the variables under the human values domain of the ESS. We included data from the following countries in our study (in alphabetical order): Austria, Denmark, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, Norway, Sweden and Switzerland. We used three variables from all eight rounds of ESS data collected every two years since 2002 (2002–2016) to correspond to one of our three concepts of interests, as defined by Klafki above. The ESS questionnaire related to human values includes short verbal portraits describing a person’s goals, aspirations or wishes that point implicitly to the importance of a single value type. Respondents are asked to compare the portrait to themselves: ‘How much like you is this person?’ The portrait: ‘It is important to him/her to be rich. He/she wants to have a lot of money and expensive things’ describes a person that according to Schwartz (2003) cherishes power values. In short, the portrait responses capture a person’s values without explicitly identifying those values.

The first variable (Impfree) builds upon the question of how important it is for the respondent to make his or her own decisions and be free: ‘Item 11: It is important to him to make his own decisions about what he does. He likes to be free to plan and to choose his activities for himself’. The item thus uncovers a person’s evaluation of independent thought and action and choosing ideas about creating and exploring; we use it as a proxy for self-determination that is described through persons’ autonomy, self-activity and independent decision making.

Second, respondents were also asked to see themselves in relation to persons showing that it is important to be loyal and close to others: ‘Item 18: It is important to him to be loyal to his friends. He wants to devote himself to people close to him’ measures preservation and enhancement of the welfare of people with whom one is in frequent personal contact. We have used this for the second variable (Iplylfr) as proxy for co-determination determining persons’ common cultural, social and political relations.

To operationalise the third item – solidarity – a variable measuring universalism (Ipeqopt) was applied. Respondents were asked to position themselves in comparison to a person who thinks that it is important that every person in the world is treated equally and believes that everyone should have equal opportunities in life. In doing so we capture not only individuals’ attitudes, but also their views towards collective rule of action by focussing on inclusion, responsibility and welfare. In short, this item addresses a person’s commitment towards people deprived of such opportunities.

Despite some critique (see e.g. Davidov, 2008), research shows that operationalisation by the Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz, 2003) seems to be applicable across countries.

In the first step of our analysis, descriptive quantitative analyses were performed to address the first research question on how countries compare across the relevant concepts of the study. In line with our theoretical framework, we focussed on 9 out of 36 countries covered by the ESS survey: Austria, Switzerland, Germany, Denmark, Norway, Sweden and Finland as Continental/Nordic Europe and Didaktik/Bildung influenced countries and Great Britain and Ireland as Anglo-Saxon Europe and curriculum tradition influenced countries. The grouping follows Tahirsylaj’s (2019) approach, where Didaktik and curriculum countries are categorised based on four criteria: historical, cultural, empirical and practical. The historical criterion relates to the historical development of the Didaktik tradition within German-speaking contexts in continental Europe, which then spread to the rest of continental and northern Europe, while the curriculum tradition emerged in the United Kingdom and then spread to other English-speaking countries. The cultural aspect relates to prior studies on world cultures, and more specifically the Global Leadership and Organizational Behaviour Effectiveness research project (GLOBE), which grouped world countries into ten cultural clusters based on data from surveys aimed at understanding organisational behaviour in respective societies (House et al., 2004), and the countries included in the present sample fall into Anglo-American, Germanic, and Nordic clusters accordingly, with Germanic and Nordic clusters forming the Didaktik countries, while the Anglo-American cluster is represented by curriculum countries. The empirical criterion relates to empirical evidence from educational studies related to intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) values across schools within countries, which show that the cultural clusters from world culture clusters referred to above could be a potential way to differentiate these clusters in terms of within-country school differentiation (Zhang et al., 2015). The practical element refers to the earlier Didaktik-curriculum dialogue that took place during the 1990s when two groups of scholars were involved – scholars and researchers representing Didaktik that included both German and Nordic scholars, and curriculum experts that included scholars mainly from the United Kingdom and the United States (Gundem & Hopmann, 1998).

Next, we created a factor score of Bildung with a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1 combining the items used for self-determination, co-determination and solidarity. We then applied factor analysis using varimax-rotated method to test whether, overall, all three items together showed any variation between Didaktik and curriculum countries. This procedure allows for creating new continuous variables based on observable Likert-scale items, which in turn makes it possible to include the newly created variable as a dependant variable in a regression model. Cross-country mean comparison and two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test between Didaktik and curriculum groupings were used to address the first research question. Table 1 provides a description of the key and independent variables used in the study.

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | FULL DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| Dependent variables | |

| Self-determination | Important to make own decisions and be free (0 to 4 scale where 0 = “Not like me at all & Not like me”; 1 = “A little like me”; 2 = “Somewhat like me”; 3 = “Like me”; and 4 = “Very much like me”) |

| Co-determination | Important to be loyal to friends and devote to people close (0 to 4) scale where (0 to 4 scale where 0 = “Not like me at all & Not like me”; 1 = “A little like me”; 2 = “Somewhat like me”; 3 = “Like me”; and 4 = “Very much like me”) |

| Solidarity | Important that people are treated equally and have equal Opportunities (0 to 4 scale where (0 to 4 scale where 0 = “Not like me at all & Not like me”; 1 = “A little like me”; 2 = “Somewhat like me”; 3 = “Like me”; and 4 = “Very much like me”) |

| Bildung score | Factor score with mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 generated with varimax-rotated method combining self-determination, co-determination and solidarity |

| Independent variables | |

| (1) Gender | Female = 1; Male = 0 |

| (2) Age | Age in years |

| (3) Citizenship status | Yes = 1; No = 0 |

| (4) Years of full-time | Number of years education completed |

| (5) Employment status | Employed = 1, Not-employed = 0 |

| (6) Employment status | Self-employed = 1, Not-employed = 0 |

| (7) Belonging to a particular religion | Yes = 1; No = 0 |

| (8) How religious are you | From 0 = “Not at all religious” to 10 = “Very religious” |

| (9) Belong to a minority | Yes = 1; No = 0 |

| (10) More education | Improve knowledge/skills: course/lecture/conference, in last 12 months (Yes = 1; No = 0) |

In the second step of the analysis – and to address the second research question – we relied on multiple regression methods to test which factors are associated with Bildung score as the dependent variable. Independent variables for these analyses are drawn mainly from the respondent’s background, including: (1) gender, (2) age, (3) citizenship status, (4) years of full-time education completed, (5 & 6) employment status as employed and self-employed, (7) belonging to a particular religion, (8) how religious are you, (9) belonging to a minority group, and (10) more education received in last 12 months (descriptive statistics of these variables are available upon request). The selection of the independent variables was arbitrary for exploratory purposes and in no way exhaustive, but the list includes variables that are routinely used in quantitative education research (see e.g. Tahirsylaj, 2019) while still being limited to variables available in the ESS datasets. The base form of the multiple linear regression model is as follows:

Bildung scorei = β0 + β1x1i + … + β10x10i+ ei(1)

where β0 is the constant for the model, β1x1i to β10x10i represent the independent variables included in the model and ei is a respondent-specific error component. The model was run for each of the countries included in the study sample from all ESS rounds. All eight ESS rounds of data from 2002 to 2016 are explored in this study for all countries from which data were available in the ESS international dataset (e.g. Denmark did not participate in the latest 2016 ESS round). List-wise case deletion was applied for missing data, and appropriate design and sampling weights as suggested by ESS documentation were applied when running the statistical analyses and models to obtain unbiased estimates.

Results

Means of self-determination, co-determination, solidarity and Bildung across countries

In the following section, the results obtained through Stata software pertaining to the first research question on the comparison between Didaktik and curriculum countries in terms of self-determination, co-determination, solidarity and Bildung are presented. Then the results related to the second research question on factors associated with Bildung are shown.

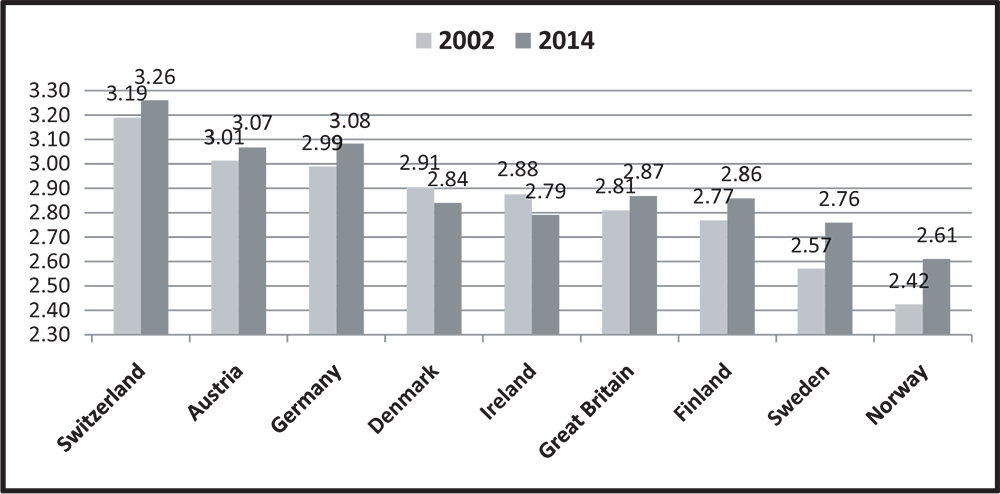

Figure 1 shows the mean scores of self-determination for each country, a variable coded on a scale from 0 to 4. Only results from ESS1-2002 and ESS7-2014 are shown here to avoid redundant information on otherwise over time stable and similar results; the results for other ESS rounds are available upon request. On this scale, a higher mean indicates that, for the respondents of a given country, it is important to make their own decisions and be free, and that they share that value.

A two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test (also known as the Mann–Whitney two sample statistic) was used to compare Didaktik and curriculum countries as two groups because the data are of an ordinal nature and a t-test cannot be applied. According to the results, Didaktik countries have a higher sum of ranks compared to the expected rank sums under the null hypothesis than curriculum countries, and there was a significant difference of z = 6.53 with p<0.001 in ESS7-2014. The z-value is higher than 1.96 which means that the null hypothesis of no difference between the two groups of countries can be rejected. Taken together, the result indicates that, on average, respondents in Didaktik countries share higher levels of self-determination than respondents in curriculum countries. In ESS1-2002, Wilcoxon rank-sum test results showed higher sum of ranks for Didaktik than curriculum countries, but the difference was not statistically significant (z = 0.95 and p>0.05).

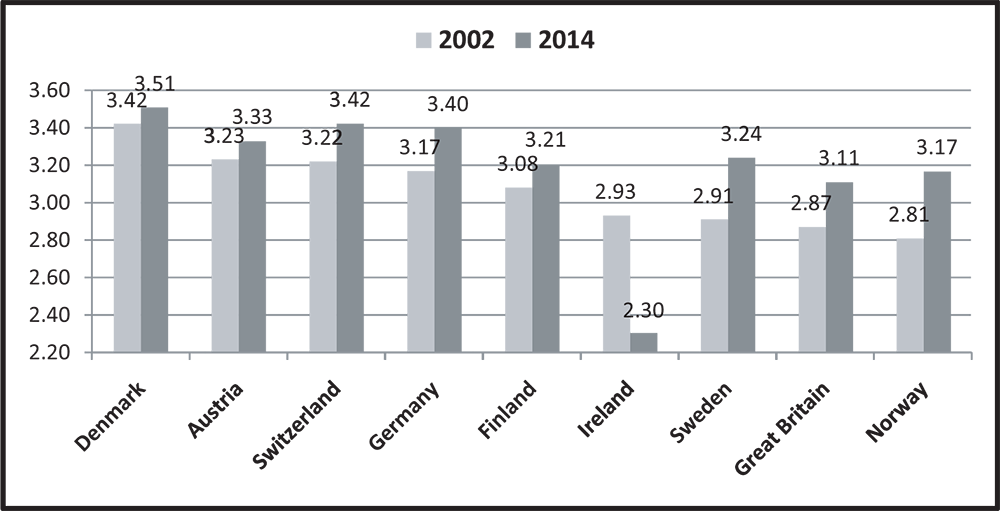

In Figure 2, mean country scores in ESS1-2002 and ESS7-2014 for co-determination are shown. Here, a higher mean value indicates that, for respondents of a given country, it is important for people to show commitment towards people deprived of such goods and to devote oneself to other close people, and that they share that value.

Overall, almost all countries, with the exception of Ireland, report higher mean values for this variable than for the other two variables. Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test resulted in Didaktik countries having a higher sum of ranks compared to the expected rank sums under the null hypothesis than curriculum countries, and there was a significant difference of z = 18.12 with p<0.001 in ESS7-2014. Similar results were found with ESS1-2002 data with a statistically significant difference of z = 12.22 and p<0.001 in favour of Didaktik countries.

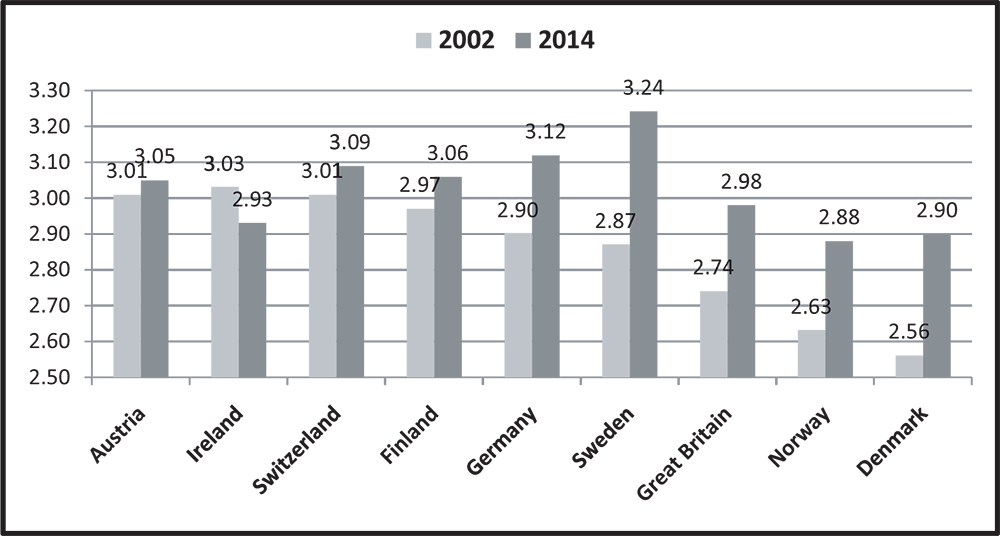

Figure 3 shows the mean country scores in ESS1-2002 and ESS7-2014 for the proxy for solidarity. A higher mean value indicates that, for respondents of a given country, it is important that people are treated equally and have equal opportunities, and that they share this value.

Here, we observe that the mean scores show a higher variation between 2002 and 2014 in five of the nine countries, namely Germany, Sweden, Great Britain, Norway and Denmark, where in 2014 respondents reported higher associations with the solidarity value. Two-sample Wilcoxon rank-sum test resulted in the Didaktik countries having a higher sum of ranks compared to the expected rank sums under the null hypothesis than curriculum countries, and there was a significant difference of z = 6.59 with p<0.001 in ESS7-2014. In ESS1-2002, the curriculum countries had higher sum of ranks than Didaktik countries, but the difference was not statistically significant of z = −1.77 and p>0.05.

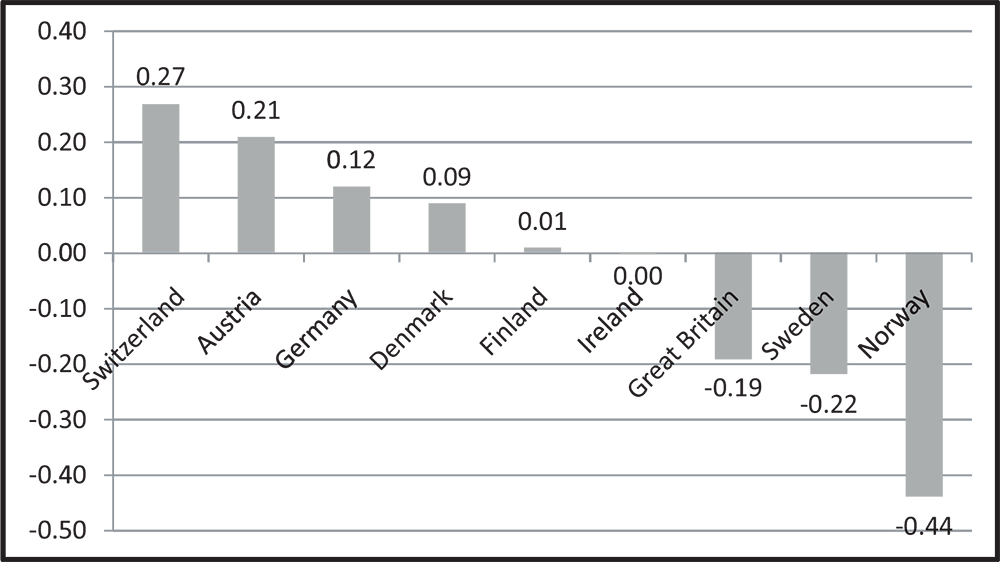

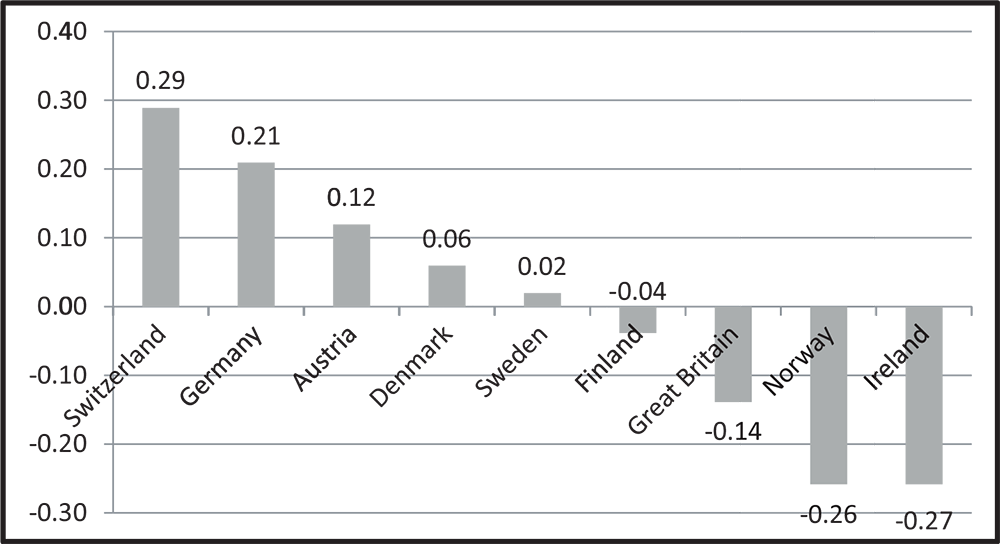

Next, in Figure 4 and Figure 5, the mean country scores for the Bildung factor score as a composite of self-determination, co-determination and solidarity in ESS1-2002 and ESS7-2014 are presented.

In ESS1-2002, the three Continental Europe and Didaktik countries, namely Switzerland, Austria and Germany, had the highest positive values. T-test results comparing the means of Didaktik and curriculum countries as two groups showed that the mean was higher for Didaktik countries, and the difference was statistically significant, where p<00.1; t = 6.42; and degrees of freedom = 17,383.

As in ESS1-2002, the means of the Bildung factor score in ESS7-2014 were the highest for the three Continental Europe and Didaktik countries – Switzerland, Austria, and Germany. Overall, t-test results comparing Didaktik and curriculum groupings showed the mean was higher for Didaktik countries, and the difference was statistically significant, where p<00.1; t = 16.30; and degrees of freedom = 17,603.

To paint an overall picture regarding our first research question, Table 2 summarises the differences in Bildung scores between Didaktik and curriculum traditions in all eight rounds of ESS data.

| ESS1-2002 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Significant) |

| ESS2-2004 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Not Significant) |

| ESS3-2006 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Significant) |

| ESS4-2008 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Not Significant) |

| ESS5-2010 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Significant) |

| ESS6-2012 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Significant) |

| ESS7-2014 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Significant) |

| ESS8-2016 | Didaktik Higher (Statistically Significant) |

In line with our hypothesis, the Bildung values were indeed higher for Didaktik than for curriculum countries in all ESS rounds, and the difference is statistically significant in all but ESS2-2004 and ESS4-2008.

Factors associated with Bildung across countries

Now, we turn to the exploratory second research question on potential factors associated with Bildung across countries, where a non-exhaustive list of 10 independent variables were examined in a series of within-country multiple linear regression models. Only the results for ESS7-2014 are shown here; the rest of the results are available upon request.

Because the dependent variable of Bildung is a factor score, the estimates of independent variables (β1 through β10) need to be interpreted as either having a positive or negative association with Bildung (i.e. a one unit increase in any of the independent variables is associated with an increase or decrease in Bildung score). Overall, the results were underwhelming for the exploratory question for ESS7-2014 shown here, as well as in other ESS rounds, as there were only a few cases where the independent variables statistically and significantly associated with the Bildung proxy. R2 values were dramatically low across countries ranging from 0.03 to 0.05, indicating that the model only explained between 3% and 5% of the variation in Bildung scores, leaving a larger chunk of 95% of the variation unexplained. This is not surprising, considering that influential factors are difficult to locate in social science research – including education – and because socio-economic status (SES) largely explains educational outcomes, but the SES variable was not available for inclusion in our models.

Examining independent variables individually, the results show that being female (β1) is positively and significantly associated with Bildung proxy in all nine countries, indicating that, on average, females share higher human values associated with Bildung than males in all countries included in our sample. Age (β2) was significant and negative only in Switzerland, Norway and Great Britain, and positive and significant only in Sweden, and not statistically significant in the others. This indicates that, in some countries, as respondents grow older, they report lower values of Bildung proxy. From an educational perspective this is explained by older respondents being more removed from the primordial educational experiences of their formal schooling. Interestingly, citizenship status (β3) was significant and positive only in Sweden, while in all other countries it was non-significant, indicating that irrespective of citizenship status, respondents within the countries on average shared the same levels of Bildung values. Years of education (β4), as expected, was positive and significant in all countries but Norway and Ireland, showing that if respondents had completed more years of full-time education, on average, they shared higher values associated with Bildung proxy. The employment status variables of being employed and self-employed (β5 and β6) when compared with the reference group of being non-employed were both positive and significant in the two curriculum countries of Great Britain and Ireland, and positive and significant only in Denmark among Didaktik countries when respondents were self-employed, and negative and significant only in Austria when respondents were employed. Two religion-related variables (β7 and β8) were significant only in Austria (both) and Ireland (belonging to a religion), indicating that, overall, religion was not associated with Bildung proxy as per the model fit and covariates included in the analysis. Belonging to a minority group (β9) was positive and significant only in Great Britain and not significant in all others. More education (β10), by improving knowledge/skills through a course/lecture/conference in the last 12 months, was positive and significant in four of the nine countries – namely Switzerland, Austria, Germany and Ireland – and not significant in the others. Interestingly, more education was positively associated with Bildung in the three countries that showed higher Bildung values in the first place – including Switzerland, Austria, and Germany – suggesting a stronger correlation between education and Bildung value in countries typically associated with stronger Bildung-based Didaktik education traditions. Similar trends in associations of these ten independent variables with Bildung proxy were observed across all eight rounds of ESS data.

| AUSTRIA | GERMANY | SWITZERLAND | DENMARK | SWEDEN | NORWAY | FINLAND | GREAT BRITAIN | IRELAND | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β0 (constant) | -0.32 | -0.48*** | 0.14 | -0.31 | -0.27 | 0.21 | -0.58** | -0.60*** | -0.63*** |

| β1 (female) | 0.14** | 0.15*** | 0.21*** | 0.22*** | 0.14** | 0.12* | 0.29*** | 0.14** | 0.17*** |

| β2 (age) | 0.00 | -0.00 | –0.002* | -0.00 | 0.01*** | -0.01*** | -0.00 | -0.004** | -0.001 |

| β3 (citizenship) | 0.03 | 0.16 | 0.04 | -0.04 | 0.35** | -0.13 | 0.15 | 0.02 | -0.16 |

| β4 (years of education) | 0.03*** | 0.03*** | 0.01* | 0.02*** | 0.03*** | -0.01 | 0.01** | 0.02** | 0.01 |

| β5 (employed) | -0.22** | 0.02 | −0.11 | 0.08 | −0.12 | 0.05 | −0.01 | 0.24* | 0.22** |

| β6 (self−employed) | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.01 | 0.35* | −0.02 | 0.21 | −0.00 | 0.39*** | 0.23* |

| β7 (religion) | −0.16** | 0.02 | −0.07 | −0.05 | −0.03 | 0.01 | −0.03 | −0.01 | 0.21** |

| β8 (how religious) | 0.03*** | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.00 | −0.01 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.02 | −0.01 |

| β9 (minority) | −0.01 | 0.16 | −0.13 | −0.03 | 0.27 | 0.13 | −0.08 | 0.21* | −0.01 |

| β10 (more education) | 0.14* | 0.11** | 0.18*** | 0.02 | −0.06 | −0.03 | −0.00 | 0.08 | 0.32*** |

| R2 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.03 |

| No. of observations | 1778 | 2979 | 1498 | 1473 | 1748 | 1419 | 2031 | 2193 | 2352 |

Note: *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Discussion and Conclusions

Differences and similarities between Didaktik and curriculum education countries have been studied quite extensively, albeit qualitatively, since the 1990s (e.g. Gundem & Hopmann, 1998; Westbury et al., 2000; Tahirsylaj et al., 2015). The most consistent finding in these comparisons is the presence of Bildung in the Didaktik tradition and the lack thereof in the curriculum tradition. In this study, we set out to explore the presence of Bildung among a number of Didaktik countries in comparison with two curriculum countries by applying quantitative methods using ESS datasets – hence In Search of Dimensions of Bildung in the title of the paper. If our three key assumptions hold – that is, if Klafki’s operationalisation of Bildung as a capability for the three dimensions self-determination, co-determination and solidarity captures the contents of Bildung; if our Bildung proxy based on ESS data and the Klafki approach stands; and if formal schooling truly affects an individual’s set of values, – then our results provide empirical evidence that the three dimensions of Bildung as outcomes of education are more prominent amongst the populations in Didaktik countries than in curriculum countries. Therefore, we argue that in Didaktik countries the educational practices that are in place seem to offer educational processes that end up in Bildung. It must be reemphasised that while our execution of the study is quantitative, it is entirely built upon a qualitative understanding and theorisation of Bildung.

To explore the research hypothesis that Bildung would be more present in Didaktik countries than in curriculum countries, we applied Klafki’s definitions of self-determination, co-determination and solidarity as capabilities representing a selected few dimensions of Bildung (other dimensions include cognitive, aesthetic and practical capabilities). We used Klafki not only because his work encompasses the core ideas of the pedagogical philosophy of antiquity (Aristotle), scholasticism (Master Eckhart), organology (Paracelsus) and the Enlightenment (Kant, Herder, Humboldt; Werler, 2010), but also because Klafki makes these ideas accessible to teacher education. Independent from this reasoning, the history of schooling in Central and Northern Europe reveals (Werler, 2004) that the above-mentioned philosophies of education are also reflected as the guiding concepts of school development, primarily as realised in teacher education programmes, school curricula and education laws. For about two hundred years, prospective teachers have been familiarised with these philosophies, which therefore form the core of their professional identity as well as their pedagogical practice. The school and teacher education history of curriculum countries (Curtis, 1967; Walsh, 2012; Raftery & Fischer, 2013) differs conceptually to Didaktik countries. If the central consideration of theories of teacher professionalism is correct, then teachers have had a value-forming influence on the students of numerous generations (Tenorth, 1986). The results of these generations of value-building processes can ultimately be measured using the model developed by Schwartz, which roughly covers the educational processes of three generations.

Education-related variables in the multivariate regression models in the second research question provided further evidence of their contribution to higher values for Bildung proxy in core Didaktik countries such as Switzerland, Austria and Germany, which indicates that education does play a positive role for Bildung as an outcome of education, especially in countries where the Didaktik and Bildung-based education tradition is more influential than in the curriculum countries in our sample. In other words, our results suggest that a nation’s education culture and practice makes a difference in shaping and moulding people’s values, beyond other family and/or other institutional and societal factors that are at play in any given society. In the continental European countries, as well as in the Nordic countries in the sample, Bildung as conceptualised by Klafki and its influence on teacher education programmes seems to have had and continues to have an impact on the extent to which people in these countries share the values of self-determination, co-determination and solidarity. Ultimately, based on the findings of this study, other influences beyond formal schooling on shaping human values cannot be excluded, as other confounding out-of-school factors such as political and economic systems and institutional arrangements contribute to how individuals develop and behave within a given society. Still, the evidence of our study suggests that the contribution that education makes in shaping human values must be recognised.

Next, the results suggest that a slightly different grouping other than Didaktik and curriculum might be at play, because the results of our analysis for the first research question suggested a separate cluster of Nordic countries, situated somewhere between continental Europe and the two Anglophone countries in our sample. Further, the positioning of the Nordic countries on the Didaktik-curriculum continuum suggest that Didaktik and Bildung-based education traditions might not be as strong in the Nordic countries as in continental Europe, where the Didaktik approach first originated. Norway in particular was an outlier, showing lower Bildung values consistently across all ESS rounds, and as such it requires further attention and analysis in future research. Nevertheless, it is a striking finding of our study that Bildung values were higher in Didaktik than curriculum countries, even when a country such as Norway (with lower mean values) was kept in the model. This indicates that if we had only kept the three core Didaktik countries from Central Europe (Austria, Germany and Switzerland) in the sample, the differences in Bildung mean values between Didaktik and curriculum countries would be even larger and more significant. In sum, our results suggest that Bildung as an outcome of education is indeed more present in countries where the Didaktik and Bildung tradition is more influential and that credit for a higher Bildung score in the Didaktik tradition may be attributed, at least partially, to the educational experiences individuals go through as part of their formal schooling.

Lastly, our research contributes to the discussion on the secondary use of previously collected quantitative data on the outcome of education systems (Meyer et al., 1992). Although this is not an experimental study, it used comparative data as a substitute for experimentation because actual experimentation would be impossible (Arnove et al., 1982). In doing so, we attempted to give meaning to the data and to drive a differentiated ideographic background analysis (Werler, 2011). Further, the analysis contributed to the identification of a universal, educationally induced structural context for people’s mind-sets. Through inductive control (the proxy construction), empirical evidence was obtained that reveals that growing up in a specific pedagogical environment contributes to the shaping of certain human value constellations through the work of teachers.

Limitations of the study and further research

There are a number of limitations of this study that need to be recognised. First, the data used here is cross-sectional and observational, and were not meant to show causality. Additionally, the study relied on secondary data analyses, so it was not possible to control what data were collected. The key variables used from the ESS datasets served as proxies for self-determination, co-determination and solidarity, and those three taken together as a proxy for Bildung. Further, the approach in the selection of variables applied here was straightforward in its attempts to get more directly to the three core theoretical concepts of self-determination, co-determination and solidarity based on Klafki’s definition of Bildung as a capability for these traits. In this sense, our attempt here is only a tentative approach to get to the three core concepts associated with Bildung using an empirical quantitative approach, recognising that the measures we used from ESS datasets were not originally meant to measure Bildung or its associated dimensions. In turn, future research projects could be conducted to address some of these limitations and potentially explore the topic from other perspectives.

Future research could focus on identifying other available datasets that might get closer to the concept of Bildung, or if resources are available, to collect their own data that could serve as a better measure of Bildung either as a process or outcome of education or both. Other factors related to respondent’s family background could also be tested to check whether they are better predictors of Bildung. However, the deviating results from the Scandinavian countries suggest that their school systems are guided by a culture different from but somehow similar to Bildung culture. Further research should explore more extensively the differences between Central and Northern European concepts of Bildung. Methodologically, future research projects might turn to some of the more recent quasi-experimental research methods such as propensity score matching (PSM) or regression discontinuity (RD) to point to more precise estimates of factors associated with Bildung if or when Bildung is researched through a quantitative endeavour.

Acknowledgments

A prior version of this paper was presented at the 2018 annual meeting of the European Conference on Educational Research (ECER) in Bozen-Bolzano, Italy on 4–7 September 2018, and the authors wish to thank ECER 2018 paper session participants for their comments and feedback on the earlier draft.

References

- Aristotle. (1987). The Nicomachean ethics. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books.

- Arnove, R., Kelly, G. & Altbach, P. (1982). Approaches and perspectives. In R. Arnove, G. Kelly & P. Altbach (Eds.), Comparative education, (pp. 3–11). New York: Macmillan.

- Bilsky, W., Janik, M. & Schwartz, S. H. (2011). The structural organization of human values-evidence from three rounds of the European Social Survey (ESS). Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 42(5), 759–776.

- Bos, W., Bonsen, M., Baumert, J., Prenzel, M., Selter, C. & Walther, G. (2013). Trends in international mathematics and science study 2007 (TIMSS 2007) (Version 1) [Datensatz]. Berlin: IQB – Institut zur Qualitätsentwicklung im Bildungswesen. http://doi.org/10.5159/IQB_TIMSS2007_v1

- Carratalà Puertas, L., & Frances Garcia, F. J. (2017). Youth and expectations on democracy in Spain: The role of individual human values structure of young people in dimension of democracy. Partecipazione e Conflitto, 9(3), 777–798.

- Cieciuch, J. & Davidov, E. (2012). A comparison of the invariance properties of the PVQ-40 and the PVQ-21 to measure human values across German and Polish samples. Survey Research Methods, 6(1), 37–48.

- Curtis, S. J. (1967). History of education in Great Britain. London: University Tutorial Press.

- Davidov, E. (2008). A cross-country and cross-time comparison of the human values measurements with the second round of the European Social Survey. Survey Research Methods, 2(1), 33–46.

- Davidov, E. & De Beuckelaer, A. (2010). How harmful are survey translations? A test with Schwartz’s human values instrument. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 22(4), 485–510.

- Deng, Z. & Luke, A. (2008). Subject matter: Defining and theorizing school subjects. In F. M. Connelly, M. F. He & J. Phillion, J. (Eds.), The Sage handbook of curriculum and instruction, (pp. 66–87). Thousand Oaks, California: Sage.

- Frost, J. & Brockmann, J. (2014). When qualitative productivity is equated with quantitative productivity: Scholars caught in a performance paradox [Wenn Qualität von Forschung, Lehre und Bildung mit quantitativer Produktivität gleichgesetzt wird – im Leistungsparadoxon gefangene Wissenschaftler] Zeitschrift fur Erziehungswissenschaft, 17(6), 25–45.

- Gundem, B. B. & Hopmann, S. (Eds.). (1998). Didaktik and/or curriculum. New York: Peter Lang.

- Hofmann-Towfigh, N. (2007). Do students’ values change in different types of schools? Journal of Moral Education 36(4), 453–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240701688010

- Hopmann, S. (2007). Restrained teaching: The common core of Didaktik. European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 109–124.

- Hopmann, S. T. (2008). No child, no school, no state left behind: Schooling in the age of accountability. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 40(4), 417–456.

- Horlacher, R. (2017a). The same but different: The German Lehrplan and curriculum. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 50(1), 1–16.

- Horlacher, R. (2017b). The educated subject and the German concept of Bildung: A comparative cultural history. London: Routledge.

- House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W. & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 cultures. Sage.

- Hudson, B. (2003). Approaching educational research from the tradition of critical-constructive Didaktik. Pedagogy, Culture and Society, 11(2), 173–187.

- Hudson, B. (2007). Comparing different traditions of teaching and learning: What can we learn about teaching and learning? European Educational Research Journal, 6(2), 135–146.

- Ilut, P. & Nistor, L. (2011). Some aspects of the relationship between basic human values and religiosity in Romania. Cultura, 8(2), 159–176.

- Inglehart, R. & Baker, W. E. (2000). Modernization, cultural change, and the persistence of traditional values. American Sociological Review, 65(1), 19–51.

- Inglehart, R. & Welzel, C. (2005). Modernization, cultural change and democracy. New York, Cambridge University Press.

- Jowell, R., Kaase, M., Fitzgerald, R. & Eva, G. (2007). The European Social Survey as a measurement model. In R. Jowell, C. Roberts, R. Fitzgerald & G. Eva (Eds.), Measuring attitudes cross-nationally. Lessons from the European Social Survey (pp. 1–32). London: Sage Publications.

- Kansanen, P. (1999). The Deutsche didaktik and the American research on teaching. In B. Hudson, F. Buchberger, P. Kansanen & H. Seel (Eds.), Didaktik/Fachdidaktik as Science(-s) of the Teaching Profession? (pp. 21–36). Umeå: TNTEE Publications.

- Klafki, W. (1959). Kategoriale bildung. Zeitschrift für Pädagogik, 5, 386–412.

- Klafki, W. (1985). Grundzüge eines neuen Allgemeinbildungskonzepts, Neue Studien zur Bildungstheorie und Didaktik. Weinheim: Beltz.

- Klafki, W. (1995). Didactic analysis as the core of preparation for instruction [Didaktische Analyse als Kern der Unterrichtsvorbereitung], Journal of Curriculum Studies, 27(1), 13–30. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0022027950270103

- Klafki, W. (1998). Characteristics of critical-constructive didaktik. In B. Gundem & S. Hopmann (Eds.), Didaktik and/or Curriculum: an international dialogue, (pp. 307–330). New York: Peter Lang.

- Klafki, W. (2000). The significance of classical theories of bildung for a contemporary concept of allgemeinbildung. In I. Westbury, S. Hopmann & K. Riquarts (Eds.), Teaching as a reflective practice: The German Didaktik tradition (pp. 85–107). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Kulin, J. & Seymer, A. (2014). What’s driving the public? A cross-country analysis of political attitudes, human values and political articulation. Sociological Research Online, 19(1), 1–14.

- Kunter, M., Leutner, D., Terhart, E. & Baumert, J. (2014). Bildungswissenschaftliches Wissen und der Erwerb professioneller Kompetenz in der Lehramtsausbildung (BilWiss) (Version 5) [Datensatz]. Berlin: IQB – Institut zur Qualitätsentwicklung im Bildungswesen. http://doi.org/10.5159/IQB_BilWiss_v5

- Lefter, V., Dan, M. C. & Vasilache, S. (2010). Statistical analysis of the evolution of values in human resource perspectives. Economic Computation and Economic Cybernetics Studies and Research, 44(3), 5–21.

- Meyer, J. W., Kamens, D. & Benavot, A. (1992). School knowledge for the masses. World models and national primary curricular categories in the twentieth century. Bristol: Falmer.

- Meyer, M. A. (2012). Keyword: Didactics in Europe. Zeitschrift Für Erziehungswissenschaft, 15(3), 449–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11618-012-0322-8

- Meyer, M. A. & Rakhkochkine, A. (2018). Wolfgang Klafki’s concept of ‘didaktik’and its reception in Russia. European Educational Research Journal, 17(1), 17–36.

- Morrison, P. S. & Weckroth, M. (2018). Human values, subjective well-being and the metropolitan region. Regional Studies, 52(3), 325–337.

- Pantić, N. & Wubbels, T. (2012). Competence-based teacher education: A change from didaktik to curriculum culture? Journal of curriculum studies, 44(1), 61–87.

- Raftery, D. & Fischer, K. (Eds.). (2013). Educating Ireland: Schooling and social change, 1700–2000. Dublin: Irish Academic Press.

- Ravitch, D. (2010). The death and life of the great American school system: How testing and choice are undermining education. New York: Basic Books.

- Reeskens, T. & Vandecasteele, L. (2017). Hard times and European youth. The effect of economic insecurity on human values, social attitudes and well-being. International Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 19–27.

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York: The Free Press.

- Saris, W. E., Knoppen, D. & Schwartz, S. H. (2012). Operationalizing the theory of human values: Balancing homogeneity of reflective items and theoretical coverage. Survey Research Methods, 7(1), 29–44.

- Schneuwly, B. & Vollmer, H. J. (2018). Bildung and subject didactics: Exploring a classical concept for building new insights. European Educational Research Journal, 17(1), 37–50.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 25, 1–65.

- Schwartz, S. H. (1994). Are there universal aspects in the structure and content of human values? Journal of Social Issues, 50, 19–45.

- Schwartz, S. H. & Huismans, S. (1995). Value priorities and religiosity in four western religions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(2), 88–107.

- Schwartz, S. H. (2003). A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations. Chapter 7 in the Questionnaire Development Package of the European Social Survey. http://essedunet.nsd.uib.no/cms/topics/1/

- Siljander, P. & Sutinen, A. (2012). Introduction. In P. Siljander, A. Kivelä & A. Sutinen (Eds.), Theories of Bildung and growth: Connections and controversies between continental educational thinking and American pragmatism (pp. 1–18). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Sjöström, J., Frerichs, N., Zuin, V. G. & Eilks, I. (2017). Use of the concept of Bildung in the international science education literature, its potential, and implications for teaching and learning. Studies in Science Education, 53(2), 165–192.

- Tahirsylaj, A. (2019). Teacher autonomy and responsibility variation and association with student performance in didaktik and curriculum traditions. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 51(2), 162–184, https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2018.1535667

- Tahirsylaj, A. (2017). Curriculum field in the making: Influences that led to social efficiency as dominant curriculum ideology in progressive era in the U.S. European Journal of Curriculum Studies, 4(1), 618–628.

- Tahirsylaj, A., Niebert, K. & Duschl, R. (2015). Curriculum and didaktik in 21st century: Still divergent or converging? European Journal of Curriculum Studies, 2(2), 262–281.

- Tenorth, H. E. (1986). “Lehrerberuf s. Dilettantismus”. Wie die Lehrprofession ihr Geschäft verstand. Luhmann/Schorr (Eds.), Zwischen Intransparenz und Verstehen. Fragen an die Pädagogik (pp. 275–322). Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Tröhler, D. (2011). Concepts, cultures and comparisons. In Pisa Under Examination (pp. 245–257). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Walsh, T. (2012). Primary education in Ireland, 1897–1990. Curriculum and context. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang.

- Weinert, S., Roßbach, H.-G., Faust, G., Blossfeld, H.-P. & Artelt, C. (2013). Bildungsprozesse, Kompetenzentwicklung und Selektionsentscheidungen im Vorschul- und Schulalter (BiKS-3-10) (Version 6) [Datensatz]. Berlin: IQB – Institut zur Qualitätsentwicklung im Bildungswesen. http://doi.org/10.5159/IQB_BIKS_3_10_v6.

- Werler, T. (2011). Norden – made by education. Komparative dimensjoner. (The North – made by Education. Comparative Dimensions.) In J. Midtsundstad & T. Werler (Eds.), Didaktikk i Norden (pp. 22–49). Kristiansand: Portal forlag.

- Werler, T. (2010). Danning og/eller literacy? Et spørsmål om framtidas utdanning [Bildung and/or Literacy? A question about education’s future] In J. Midtsundstad & I. Willbergh (Eds.), Didaktikk. Nye teoretiske perspektiver på undervisning (pp. 76–96). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Werler, T. (2004). Nation, Gemeinschaft, Bildung. Die Evolution des modernen skandinavischen Wohlfahrtsstaates und das Schulsystem. Baltmannsweiler: Schneider.

- Westbury, I., Hopmann, S. & Riquarts, K. (Eds.). (2000). Teaching as a reflective practice: The German Didaktik tradition. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Zhang, L., Khan, G., & Tahirsylaj, A. (2015). Student performance, school differentiation, and world cultures: Evidence from PISA 2009. International Journal of Educational Development, 42, 43–53.